Yes, And... So!

Systems Thinking Distilled

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays explore common topics from different perspectives and disciplines to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic swings back to Systems Thinking, one of our foundational tools here on Polymathic Being. We keep being asked if we can further distill the concept for broader application. While there’s risk in over-simplification, let’s explore a simple mantra that anyone can use to apply Systems Thinking and unlock true innovation that balances ethics, safety, and risk.

Introduction

“Whenever I run into a problem I can't solve, I always make it bigger. I can never solve it by trying to make it smaller, but if I make it big enough, I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.“

- Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower

In today’s political, technical, and even creative world, we aren’t facing simple problems. Our society is more interconnected and diverse, and the systems that underpin our standards of living are interdisciplinary and multidimensional. These systems architectures and infrastructure challenges have cascading consequences of systems of systems failures.

There’s also a problematic tendency to over-simplify issues that ignore the nuances and result in even messier and less informed solutions. This paradox highlights the primary challenge in applying Systems Thinking: Everyone wants a simple answer.

C.J. Unis and I attempted to address this challenge in our foundational essay on Systems Thinking where we broke this powerful mindset into three elements:

The Humility to accept we don’t know as much about the system as we think.

Intentional Reframing of the problem to see if it changes (The Enemy’s Gate is Down)

We further decomposed these elements into a recommendation to look at any system from the Physical, Logical, and Persona layers to get the basics of the idiosyncrasies of what you’re trying to understand, build, or improve. It’s a framework that is adaptable enough to tackle everything from autonomy and AI to cyber warfare to supply chain resiliency.

The problem C.J. and I had was when we presented our original Systems Thinking concept to the Military Operations Research Society, the main question was how to distill the concept even further for broader application. The paradox of over-simplification was affecting even our ability to challenge the paradox.

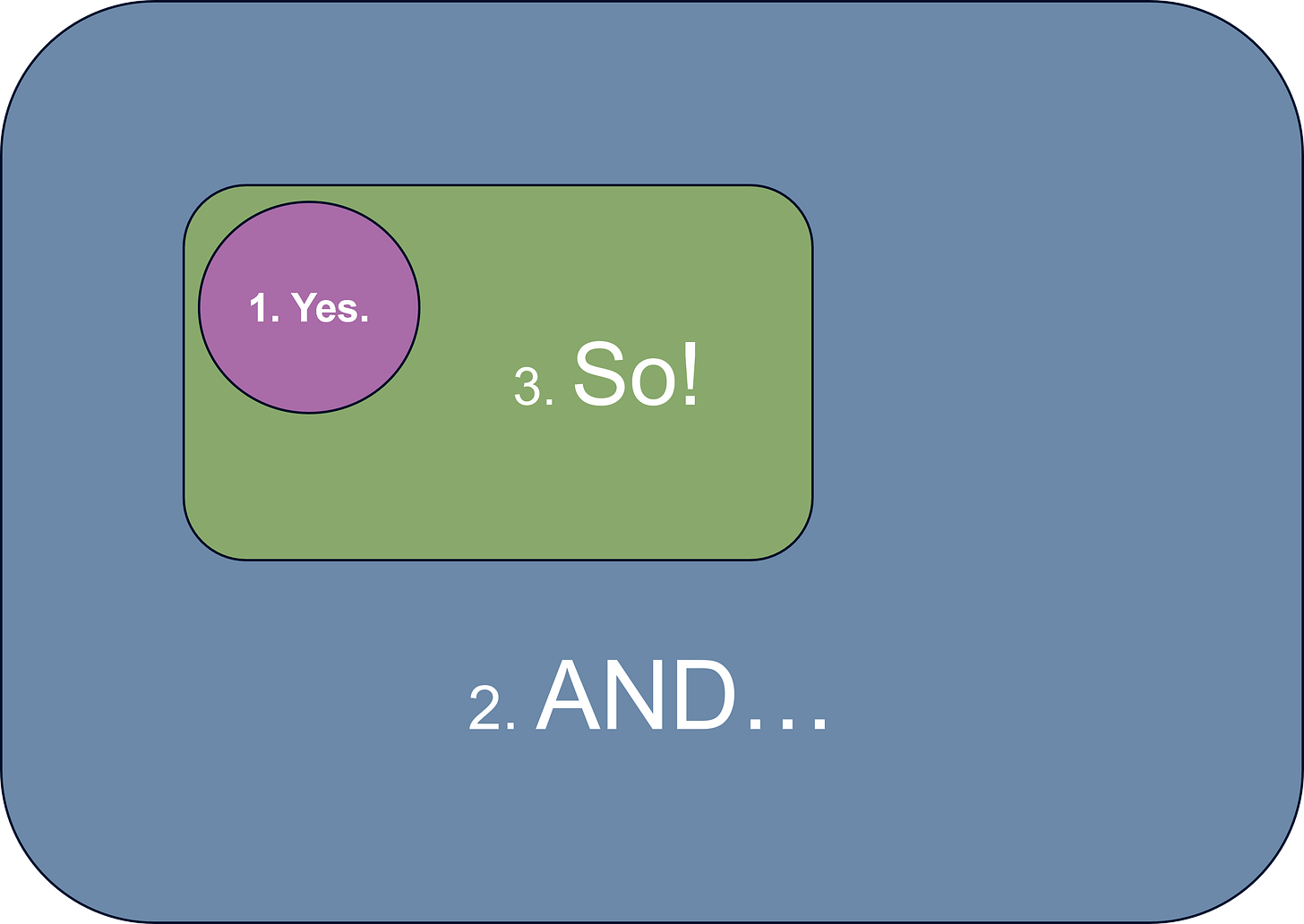

Joshua Deiches and I put our heads together trying to simplify it even further while avoiding the risk of over-simplification. We landed on a simple mantra that anyone can use to apply Systems Thinking and unlock true innovation that balances ethics, safety, and risk. We call it Yes, And… So!

Yes, Let’s acknowledge that what you are focusing on needs to be addressed.

And… We need to step back to ensure we consider critical elements in the larger system focusing on the physical, logical, and persona implications at a minimum.

So! With this larger context, what new design, risk, ethical considerations, and strategies have emerged that help achieve the outcomes you want?

Take for instance OceanGate, the micro-submarine that went to explore the Titanic and joined them instead. They literally applied a Silicon Valley Start-Up mindset that doesn’t even work for software to a high-consequence and complex system. OceanGate simplified everything and ignored the complexity to their ultimate demise.

Let’s go ahead and use OceanGate as a case study for a first-pass analysis to understand Systems Thinking using Yes. And… So!

Case Study 1: OceanGate

Yes, much of the development around space and water-based exploration has stagnated and become burdened by large bureaucratic organizations over the past 75 years.

Yes, Concepts like commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS), modular systems, and the classic Keep It Simple Stupid (KISS) all make good constraints to achieve innovation.

And… more people have been to space than have been at Titanic depths.

And… the significance of a failure in an undersea environment means the application of common Start-Up mantras like “fail early fail often,” “build it while you fly it,” and “move fast and break stuff” sound great and might work on a cloud software solution where the consequence of failure is a website that won’t load but don’t apply here.

And… COTS components are OK for a prototype or model but are not built to the exacting standards necessary to handle the pressures, high oxygen environments, or corrosive saltwater conditions.

So! it’s best to understand where to draw the line for a prototype and explicitly what critical systems need to be designed to survive at the extreme conditions expected. It might mean going slower to start with, it might cost more to get there, and it might take longer to pass the safety checks, but the pressure the OceanGate CEO put on his team to rush is nothing compared to the pressure he’s feeling right now.

There’s even more to this example such as their use of wireless game controllers, non-encapsulated wiring on the thrusters, and even bragging about using expired carbon fiber in the design (which also isn’t the right material to begin with) all of which are a function of zero real systems thinking. If they had done a few rounds of Yes, And, So, they would have been more likely to avert catastrophe.

Case Study 2 AI and Artists

Systems thinking applies to more than just pure technology. We can also apply it to problems that have very unique human considerations like the creation of Art. This is a very polarizing topic with widely divergent opinions so the oversimplification, on both sides, has created a lot of divisions and disagreements over the past two years. Let’s take a look at where we end up if we apply Yes, And… So!

Yes, Emerging AI image generators are directly threatening the livelihood of graphic artists, authors, and other creators.

Yes, Silicon Valley tech bros have used questionable acquisition of training data by scraping artists’ materials from the web in ethically problematic ways.

Yes, Some users of AI are using it to shortcut creative activities and proceed with very little empathy or consideration of artists who have dedicated their lives in the pursuit of mastery of their artistic mediums.

And… AI is one more step in a long history of technology reducing the effort it takes to produce art from Plato railing against the written word, to scribes opposing the printing press, to painters protesting photographers, and photographers lamenting cellphone cameras.

And… Technology saves time and opens the door of art to more people who either lack the time to dedicate or have physical or mental handicaps that don’t allow the expression of their creativity.

And… New technologies, like AI, allow artists to adapt, innovate, and uncover new styles that can either retain a pure human focus or embrace the technologies to expand art long into the future.

And… Many people are reacting without understanding human creativity, how art builds on others, and without a deep understanding of how art, even technology-enabled art, is created

And… Most importantly, there are elements to the artistic process that benefit the artist and benefit anyone creating art that is essential we don’t replace. We need to maintain the personal exploration, decisions, and learning that occur during creation.

So! We can consider the history of technology, the unique value of human expression, and the risks of ignorantly using AI tools without due consideration. We can then find ways to incorporate these new tools ethically and intentionally in a way that elevates humanity instead of threatening to replace it.

Conclusion

Yes, And… So! creates the simplest way to begin taking the first steps in Systems Thinking. As you allow for the And, you allow yourself, and others, to step back from the problem and add in more information. With that new information, you can better contextualize the original problem and add new considerations. So, we can have a much better understanding of the larger problem space and a more focused area in which to affect a change.

Imagine if more people took these steps when reacting to the complex problems we face. How much more common ground could we find? How many more cascading consequences could we avoid? How much less polarizing division would exist if acknowledged the problem, expanded the analysis, and found a more nuanced answer instead of the simple one? Yes, And… So!

What case studies can you add to the list? Is there something you’re struggling with that you’d like to analyze through this framework? Leave a comment or post in the Polymathic Being chat and we can collaborate to uncover new insights and solutions

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid member keeps these essays open for everyone. Hurry and grab 20% off an annual subscription. That’s $24 a year or $2 a month. It’s just 50¢ an essay and makes a big difference.

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Goatfury Writes All-around great daily essays

Never Stop Learning Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

Cyborgs Writing Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

Educating AI Integrating AI into education

Mostly Harmless Ideas Computer Science for Everyone

Your Eisenhower quote reminds me of another one in the same vein from John Muir, founder of the US system of parks:

"When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe."

https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/writings/misquotes.aspx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Muir

Kind of makes me want to go bang my head against a wall, but I’ve been healthcare adjacent for the last 20 years - lots of pent up frustration from systems un-thinking. This is a great framework for teaching the concept, but how will users know when they’ve gotten what they need out of it? Suggestion: the quality of the results depends a lot more on who is at the table for the discussion than it does on the approach that is used.