What's In A Brain?

AI, the Human Brain, and PTSD

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic looks into how our brains capture, process, store, and recall memories and how that relates to the recent advancements in AI. We’ll explore our ‘second brain', memory recall, and how this ties together with something near and dear to me; PTSD in veterans. This essay provides insight and awareness to help anyone improve their mental health and emotional regulation.

Introduction

Years ago, I was working to understand post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as it relates to my time in the military, and, in my reading, came up with a mental model of how our brain works. I was motivated to share this model due to the recent explosion of AI in every aspect of our lives and a growing belief that we are approaching Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

To step back, AGI, or general AI, is a theoretical form of AI where a machine would have an intelligence equal to humans. It would have a self-aware consciousness that has the ability to solve problems, learn, and plan for the future. This, plus the discussions of how AI is helping us understand the brain better is leading us to believe that we are close to copying human thinking. It sounds and even looks plausible, except it misses a lot of the aspects of how a brain really functions.

What’s in a Brain?

We aren’t computers, programmed with a logical process that executes in a similar manner each time. In fact, unlike ChatGPT which is a predictive, IE statistically aligned, process, humans aren’t coded like that at all!

As Jonathan Haidt explored in the wonderful book “The Happiness Hypothesis,” we aren’t rational, logical beings. We are emotional creatures with a logical component developed only recently in our pre-frontal cortex; a part of the brain that differentiates us from our closest primate cousins.

Haidt describes this as a rider on an elephant with the rider as the logical and rational brain, on the emotional, elephant brain. Clearly, if we think our logic reigns supreme, we underestimate the elephant in the room. As I like to say: social media, specifically Twitter, isn’t logical, it’s Pink Elephants on parade:

To fully appreciate how this works, we first have to understand how much of our brain and memories aren’t solely captured or influenced by the gray matter between our ears and then, how we process and store information as memories.

Our Second Brain

Adding a layer of complexity is the fact that our brain is not isolated, and our memories are not just ‘data’ as we might think. They are actually infused with a crazy cocktail of hormones as well.

The entire endocrine system has a major impact on memory, consciousness, and cognitive interpretations. The hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, the pineal gland, the thyroid gland, the parathyroid glands, the adrenal glands, the pancreas, the ovaries, and the testes are all part of how we think and how we store memories.

It’s what we call our ‘gut feeling.’ The endocrine system controls the function of the digestive system at various stages. In reality, the gastrointestinal tract is the largest endocrine organ in the body and the endocrine cells within it are referred to collectively as the enteric endocrine system.

While we don’t consciously think with our gut; subconsciously our gut thinks for us. Basically, a second brain. There’s been new research showing an unbreakable connection between gut health and mental health. If our gut is stressed with bad food or imbalanced nutrients, it floods the endocrine system with alarm bells which the brain receives and flags our ‘fight or flight’ response.

This creates a discordance if we are actually safe as most of us are in our first-world lives. While externally everything ‘feels’ safe, our gut is telling us something is wrong and so the brain freaks out. Because a threat that we can’t see is the worst thing for human survival. Historically, these were the threats that could kill you the fastest. So, the brain starts dumping alarm signals that lead to hyper-awareness and worry. What we diagnose as Anxiety.

The research being done on the connection between gut health and mental health is called psychobiotics:

Psychobiotics is the study of the mess of beneficial bacteria and the support systems we maintain to ‘farm’ these and how that influences bacteria–brain relationships. In a weird way, psychobiotics affect emotional, cognitive, systemic, and neural indices. By altering the types of bacteria in your gut, it may be possible to improve your brain health.

Our brain’s interpretation of a stimulus, and our memories’ recording of it, is heavily affected by our endocrine system. Meaning, ‘simple’ observations, when coupled with a ‘gut’ interpretation, can take on greater, or less significance than you might imagine and this leads us to investigate how our brain actually stores this information.

Memory Storage and Recall

As I mentioned, as I researched PTSD, I came up with a mental model based on my reading. This was driven by the discovery that we don’t store memories as if they were movies, able to be recalled perfectly. We store them as feelings, impacts, and objects.

Imagine there are clusters of ‘things’ that you learn. Red, blue, square, round, rough, smooth, pattern, texture, soft, hard. Then there are feelings of happiness, sadness, anxiety, nervousness, excitement, and terror. Then actions like fast, slow, roll, bounce, vibrate, etc. These are the attributes you learn which form the basis of memory recall.

We can see this with children as they grow. They don’t learn ‘ball;’ they learn sphere, smooth, rolls, and red. Only later does the vocalization of the ‘ball’ connect to the object. This is because our brains are designed to be computationally efficient. Instead of storing all the attributes of a unique thing individually, we store the core elements and then thread a ‘memory’ through the objects. So, for two balls, one smooth and red and the other bumpy and blue they would still have common underpinnings. This also just like we explored in Stereotyping Properly.

What does this mean for memories? Think of the person you know best. Close your eyes. Recall their face. Do you see a perfect snapshot? Probably not. If you do it again, you find your brain jumping to attributes. If I think of my wife, I first start with an emotion; a feeling of my ‘wife’ that helps to build out the image, I can feel my brain remembering the pattern and calling objects.

Hair: reddish blond, long, braid, thick

Face: blue eyes, angular nose/chin, athletic

Body: height, proportions, curves

Emotions: love, nurturing, humor, stubborn

Memories: actions, activities, events

I don’t have a perfect memory of every detail and neither does anyone else. Try it and see. Think hard about how you are thinking, not just the end state. Work hard to flesh out the memory as best as you can.

We use patterns to fill in the gaps and those patterns are also shared by other people. This is why we use analogies when we ever try to describe something. Because we build things off of those patterns and an analogy creates a framework, like a lattice we can use to flesh out ideas. (and yes, that was just an analogy to help you visualize)

Your memory isn’t a perfect recall of the object. It is instead, the ‘recipe’ or recall code that allows you to pull from your object stores. Recently more exploration has occurred on this topic such as an essay in Psychology Today which captures:

The human brain (and undoubtedly the brains of other animal species) can be thought of as a sophisticated pattern recognition device that we use to constantly update our working impressions—what are popularly called memories—of the world derived from our ongoing experiences as a living, breathing human being. Seen from this perspective, categorical reasoning is pattern recognition by your brain that relies on what might be called “averaged memories” that have captured only the core, or generally recurring, features of the patterning of things and events in your life. Common sense labels these generalized and often quite schematic memories as “categories,” “types,” “kinds,” and so forth.

Now imagine that you are exposed to something regularly and are forced to recall the memory often. If you constantly query that pattern, your brain builds higher volume processing flows to expedite that recall. Core memories are those that have the thickest connections or are tied to many other connections such as your sense of identity.

Conversely, forgetting isn’t losing the foundational elements, it’s merely losing the pattern through a lack of reinforcement or recall. Often this is why, when talking about some acquaintance we’ve forgotten, the conversations sound a lot like:

“Remember Joe from when we first started work?”

“No? who was Joe?”

“He had that blue BMW and worked in IT.”

“I don’t recall that, was he the burrito guy?”

“No, that was Frank. Joe was the one who dumped that girl during happy hour.”

“Was he that short kid with the Napoleon complex?”

“Yeah! He was always walking around with a chip on his shoulder.”

“Right! He got fired a week later for trying to bust into that girl’s social media account using company systems!”

“Oh yeah, that’s right, I’d forgotten that.

And once the recipe is re-established, suddenly more memories begin to be woven back together that wouldn’t have been possible without rebuilding the pattern. These two characters could probably spend the next hour rebuilding an entire memory deck through mutual reinforcement that both of them only partially remembered.

Tying it all back together

Our brains are a holistic fusion between our actual gray matter and our gut. Our memories are a recall code of common objects infused with hormonal impact and response. Not too easy to tease apart, and definitely hard to emulate with computers.

So what does this mean for PTSD? Well, simply put, PTSD is a gut response that increases the connectivity between memory objects. For example, we all have attributes of driving, roads, garbage bags, and rubbish. By themselves, they are all innocuous things.

Now imagine that you spend a year in Iraq where garbage bags are used to hide improvised explosive devices(IEDs) among rubbish on the sides of the road. Add in the risk of actually getting blown up while driving because you missed a warning signal.

This results in your brain being hyper-focused on that threat. Basically there’s a mental super-highway connecting those attributes, spiced with the hormonal response of anxiety and fear. Pull the Soldier out of Iraq and put them with their family on vacation driving down the highway and what happens? When they see a garbage bag amidst rubbish along the highway their system crosses that super-highway of emotion and it’s much more likely that they’ll get sucked down a different path.

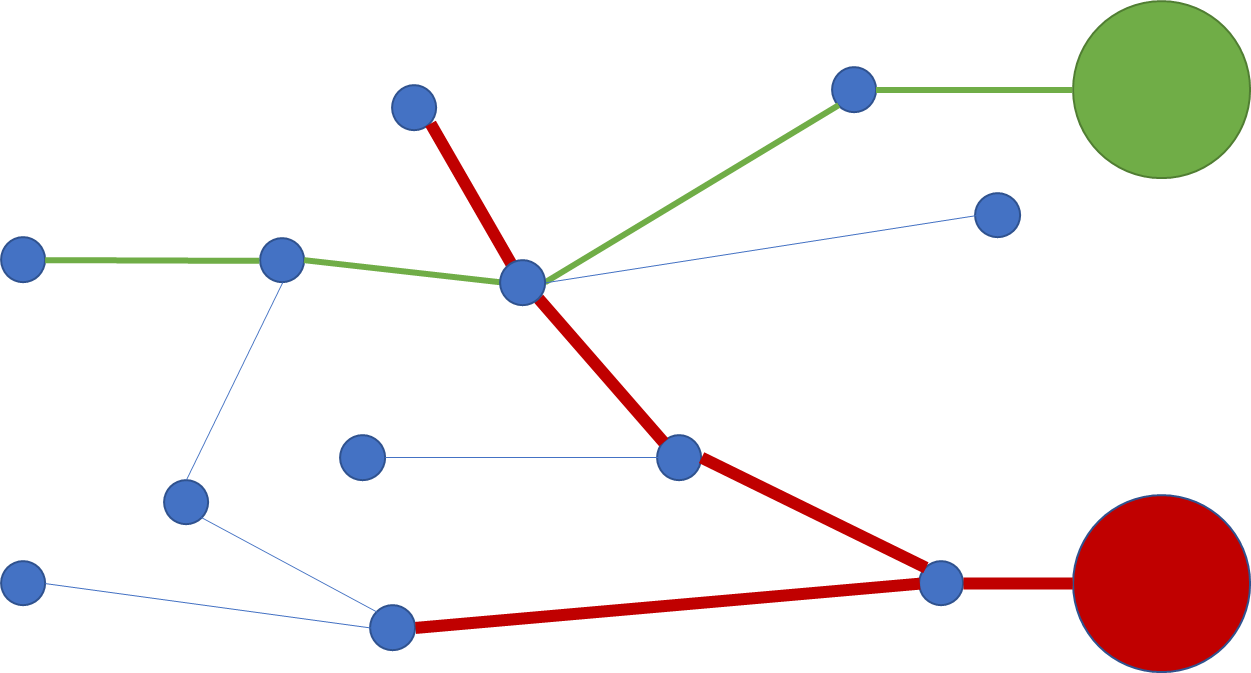

This is like the image below where they are moving down the green path. When your brain hits garbage bag and the red super-highway of emotions and risk, it’s hard to get across to the innocuous (green) instead of being brought down the path toward a panic attack (red). This is why, much of PTSD treatment is in cognitive behavioral therapy by continuing to expose the patient to stimuli to reprogram the trigger from red to green.

Albeit simplified, this model helps to understand how the brain works, how our emotions are linked to it, and how to become aware of the connections that can suck our attention toward negative thoughts and emotions. I’ve learned to pay attention to these trigger points and notice when I feel the pull toward problems and am able to put up guardrails to keep myself on the path I want.

Conclusion

We are emotional creatures with two brains and a complex and interconnected memory system. While advancements in AI can mimic elements of how we think, it is unlikely to capture the essence of what it means to be a human thinking these things. Doing so requires a fusion of neuroscience, biology, endocrinology, and many more disciplines to solve and we are a long way away.

Yet, while we don’t have to worry about AI emulating this soon, it’s important that we focus on how these concepts can help us understand who we are, how we think, and why we interpret and recall memories differently. In doing so we can regain and maintain improved control over our mental state and learn how our reality can differ from those around us. (this also helps us in knowing how we are interpreting what AI is doing so we can better understand it)

I’d love your thoughts and comments on how this can apply to you, or how you’ve found this working in your lives. Also, since this is pretty nascent research, I’d love if you shared new information we can start to use to better understand ourselves and others.

New annual subscriptions for 20% off!

This essay became a foundational element for my debut novel Paradox where the protagonist Kira and her friends puzzle through what AI really is in Chapter 3.

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further Reading from Authors I really appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares

Looking for other great newsletters and blogs? Try The Sample

Every morning, The Sample sends you an article from a blog or newsletter that matches up with your interests. When you get one you like, you can subscribe to the writer with one click. Sign up here.

Also, if you have a newsletter you would like to promote, they offer a great service that gets your writing out there to a new audience.

Nicely put. I’m a trauma survivor too and have been learning slowly to recognize those triggers and my brain-gut connection. Perhaps as a result of this more nuanced appreciation of how our brains work, I’m less worried than my colleagues in tech that AI is on the verge of putting us all out of work.

Have you read “Body Keeps the Score”? I’ve got tons of personal experience with the way our body holds information our minds aren’t yet ready to process...it’s fascinating and has led me to think our entire body has intelligences of various sorts, right down to our feet.

It’s a fascinating topic. Thanks for sharing.

Very refreshing to read a piece like this. In my experience AI enthusiasts rarely seem to focus on the unique complexity of the human mind and body compared to AI programs and instead focus on the increasing 'intelligence' of these programs. It also strikes me as odd that improvement in the intelligence of AI should correspond to a conscious AI. Chickens aren't the brightest among us but we can probably agree that they are conscious.

I've also been interested in learning more about PTSD and your insights are greatly appreciated. I'm looking forward to reading more.