Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic explores some interesting stories from my time in the Army and how those lessons apply to my work in the professional world. This intentional reconceptualization of The Enemy’s Gate is Down has also become one of Polymathic Disciplines’ key elements in Systems Thinking and so it’s appropriate to dive deeper in. This essay was originally published in the Military Operations Research Society (MORS) quarterly magazine PHALANX - The Magazine of National Security Analysis in their Fall 2022 issue. It is reprinted here with only minor formatting changes.

Introduction

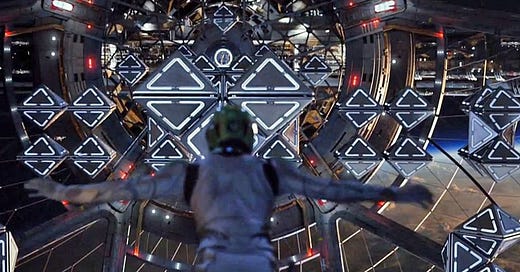

The 1985 science-fiction story Ender’s Game is a future wargaming story where Earth prepares to battle an alien force. The protagonists, led by the titular Ender, have created an international fleet with a dedicated battle school to train exceptionally gifted children in complex warfighting techniques against an advanced enemy in a domain that is still nascent to human experience. The battle school challenged cadets mentally and physically, then rigorously tested them to find a winning strategy for a type of war that had never been fought against an enemy about which virtually nothing is known. To succeed, it required reconceptualizing the strategy and tactics to yield insights and concepts outside of the traditional realms of warfare.

Like in Ender’s Game, warfare in the 21st century presents new and dynamic problems that are difficult to solve with traditional perspectives or paradigms of analysis. Solutions often fall victim to common pitfalls where the expected answers are more technology, more complexity, and the drive to do something new or different.

Operations Research (OR) is the profession best positioned to answer these challenging questions due to the natural breadth of analysis disciplines it encompasses, the analytical tools it leverages, and the diversity of experience that analysts hold. Leveraging this core strength of operations research and pairing it with the insights from Ender’s Game enables analysts to step back and reframe the 21st century warfare problem sets from different perspectives, applying lessons learned and established methods, and focusing on simplicity.

I first read this book in 2003 as a cadet in ROTC while Operation Enduring Freedom was in full swing and Operation Iraqi Freedom was kicking off. The lessons I learned in this book were fundamental to my success as a junior Army officer in both combat and garrison roles and subsequently in my career as an Operations Research (OR) analyst. The following are a series of personal case studies I’ve experienced in my career that demonstrate the power of reframing a problem.

Foundational Case Study: The Enemy’s Gate is Down

“It was impossible to tell, looking at the perfectly square doors, which way had been up. And it didn’t matter. For now Ender had found the orientation that made sense. The enemy’s gate was down. The object of the game was to fall toward the enemy’s home.”

- Ender’s Game

The battle school in Ender’s Game has a training lab where the cadets participate in competitive war simulations in zero gravity. Given the entrances to the lab, it was easy to view the battle field as looking across the Battle Lab. This conceptualization led to established and therefore, predicable, tactics where teams continued to compete but margins of victory were slight and the nature of the competitions was stagnant. Ender recognized that, in zero gravity, the concepts of up, down or across are completely arbitrary and based on terrestrial experience which can be limiting in space. Ender reframed the idea that the enemy’s gate was down and in doing so transformed the nature of how the battle was conducted.

As Ender began challenging the paradigm, he developed a team around him that also provided non-traditional suggestions. As Ender’s unit succeeded, the battle school leadership continued to change the nature of the competition with increasingly difficult and unfair games. Ender’s team was forced to continuously improve the best practices and be adaptable in force structures, tactics, techniques, and tools. These frequent reconceptualizations enabled Ender and his team to dominate the battle lab and eventually be selected as the strategy team leading the war against the alien force.

The lessons I learned from this example are:

People orient themselves to what feels normal or comfortable

By changing the perspective of how you view an object you can open numerous possibilities

Once you’ve challenged the possible, you start to re-think everything you’ve been told is ‘right’

You should surround yourselves by those who continue to challenge the prevailing paradigm and leverage their insight to supplement your own

In applying these lessons, one technique that works well is to intentionally step back and look at the problem from a bigger perspective. As General Dwight D. Eisenhower is quoted as saying: "Whenever I run into a problem I can't solve, I always make it bigger. I can never solve it by trying to make it smaller, but if I make it big enough, I can begin to see the outlines of a solution.“ This intentional reframing can assist us in checking our own cognitive biases and assumptions and provide additional angles to consider for analysis.

I used this technique with an analysis team struggling with large volumes of data and the different perspectives stakeholders had on what story the data was telling. Design engineering was looking from one perspective, program management another, quality engineering a third, the manufacturing floor a fourth, and so on through each stakeholder. We were suffering from a forced perspective akin to visualizing the enemy’s gate as across. The key was to recognize there were multiple perspectives and to view the data in three dimensions. This view of the data was achieved using graph visualization of nodes and edges creating the dimensions and then observing the different viewpoints on the data.1

This “polyhedronic data analysis” allowed the application of multiple analysis techniques that could work in concert while capturing the assumptions of the stakeholders and deconflicting them from other perspectives. In this way the team succeeded in performing valuable analysis on complex data.

Case Study 1: IED’s Are Not New

As a new 2nd Lieutenant in 2005, the threat of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) was one of the foremost concerns in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The prevailing theme was that these were new tactics, that there were limited ways to mitigate them, and, even worse, that there wasn’t much that soldiers could do but hope and pray.

In 2007, I participated in a National Training Center rotation with the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment in preparation for a deployment to Iraq that fall. The training lanes represented typical combat scenarios complete with IEDs, ambushes, etc. At this time, the solutions to IEDs were presented as a blend of technology and persistent observation for things that appeared out of the ordinary. These tactics bothered me as too reactive and worried me because, in these training lanes, I got ‘blown up’ a few more times than I was comfortable with.

Deploying to Iraq in late 2007 brought the threat to home as I was now no longer in the hypothetical or theoretical; I was in the environment where my peers and friends were being killed by real IEDs. The solutions to the problem continued to resort to technology. Huge rollers, jammers, passive infrared triggers, more armor, and Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles. These were still reactive measures, albeit sophisticated, that were easily thwarted by the insurgents using unsophisticated countermeasures or adapting their tactics.

The crucible that changed my perspective was working with a new soldier as I led missions for a police transition team. This soldier was terrified of the threat, not because of the concept of battle and death, but of the helplessness that was instilled as a function of these reactive solutions.

That’s when it hit me; a growing frustration in the back of my head manifest itself. The answer was right in front of us: IEDs are not new; they are as old as the emergence of mine warfare. The Army has been producing documentation on creating IEDs for decades using available materials in non-traditional ways.2 Drawing a page from the Ranger Handbook, an IED is merely the mass-casualty effector of a classic ambush, no different from a claymore, landmine, or other explosive device.3 Furthermore, once we reconceptualized the IED as a function of a traditional ambush, the solution was already on hand. First, tactics are established for how and where to conduct an ambush and second, we have battle drills for how to react to them.

The team pulled out maps, plotted our routes and then analyzed, from the insurgent’s perspective, where they would conduct an ambush to maximize the effectiveness. We’d mark those locations, adjust the route if necessary, and then if they were unavoidable, increase our force posture to present a less susceptible target as we approached those locations. Being a hard target reduced the risk of engagement while at the same time, increased the potential for successful reaction to an ambush. With these proactive techniques, the police transition team was never successfully engaged by an IED while successfully identifying and reducing several.

Rethinking the paradigm of IEDs allowed the team to transition from a reactive and technology-heavy mitigation, to a proactive and tactics-based success. IEDs are not new and neither are the methods to avoid them.

The lessons I learned from this example are:

Problems are not always unique or new; always look for the commonality of your problem to others to find proven solutions

The solutions to problems are not always technology

Technology solutions can often distract from simpler, tactics-based solutions

Reliance on technology will never overcome poor force posture

Dan Ward covers this topic in his book F.I.R.E. – How Fast, Inexpensive, Restrained, and Elegant Methods Ignite Innovation. In Chapter 2 he explores how many of our research problems actually include groups of known problems with known answers and much of what is new is merely in application. By leveraging these known problems and answers we can construct a solution space quickly and provide elegant solutions.4

In application these lessons involve stepping back and contextualizing around common problems, tools, and solutions. Identifying an 80 percent solution based on commonality decreases the effort for the 20 percent that may be new or unique. In doing so an analyst can respond to customers with quick solutions and targeted analysis.

Case Study 2: How Smoking Saved My Life

Deployed with a police transition team in northern Iraq, two things are ubiquitous when working with Iraqi police: Chai (tea) and cigarettes. Both have a great degree of tradition and an underlying interpersonal relationship in the local culture. In my role of assisting and training the police forces, social interaction was critical to the Iraqis prior to “getting down to business.” Adding to this challenge was that troop rotations eliminated continuity for the Iraqis and recent police on soldier attacks had injured and killed several soldiers in Mosul. However, developing these relationships was still crucial to the success of the mission.

The Iraqi police had an affinity for American cigarettes and so I sourced a few cartons for distribution. I provided packs to my soldiers with the direction that when they took a smoke break, they were expected to invite any nearby police officer to join them for a cigarette. The goal was simple; smoke and joke. In doing so, it provided opportunities for my soldiers to get to know the humans they were dealing with and for the Iraqi police to get to know the humans I led. When possible, I left an interpreter with them to assist but often the conversations had to rely on pantomiming and sharing of photos in lieu of robust dialog to create a relationship.

Similarly, when I’d sit with police leadership and was offered a cigarette, I’d accept, sit back, and ask questions that had nothing to do with my mission. In this manner, I learned a lot about the Iraqis I relied on for my success. Did you know that Col. Salim was a fighter pilot in both the Iran/Iraq and Desert Storm Wars? Isn’t it interesting that General Ibrahim has a son studying in the States? Who knew that Officer Mostafa was a Patriots American football fan? This style of relationship is often overlooked and yet is critical to achieving the mission.

One success story was sitting with General Ibrahim, drinking Chai, and finishing a cigarette while chatting, in English, about nothing important. The door of the office burst open and one of my senior ranking counterparts strode in, addressed the general, and began articulating his needs. General Ibrahim, in Arabic, answered the questions and concerns. Soon my counterpart exited and General Ibrahim looked at me, takes a draw on his cigarette, and in fluent English said, “He’s kind of an ass, isn’t he?” He thought for a moment and asked me to confirm what needed to be done, then he looked at me and said, “For you I will do it.” And he did.

A second success was when one of my new soldiers came running up to me and exclaimed “Sir, I was told that we shouldn’t go down Route Rat!” The soldier explained that, while smoking with an Iraqi police officer he had developed a friendship with, the officer went quiet and then leaned over and said, “Don’t go down Route Rat.” When my soldier asked for clarification the officer responded, “I like you…don’t go down Route Rat.” When we looked at our route home, the typical path took us on Route Rat for less than a kilometer. We called up route clearance, reported the location and bypassed that section. Sure enough, route clearance found an IED on that stretch of highway.

The lessons I learned from this example are:

People who like you don’t like the idea of you getting hurt.

Humanizing the people you work with allows you to make more friends than enemies

You can get good intel from unlikely sources

In application, the fundamental point is to never overlook the human implications of your analysis. An axiom I’ve crafted over the years is that “the fastest way to fail is to think you can, or should, do it by yourself.” Sometimes it is the water-cooler conversation that helps shift your perspective and give you that insight you otherwise wouldn’t have had. This is supported by the cognitive science literature as well. As Joseph Henrich studied by comparing humans and chimpanzees, the key isn’t in IQ but in social intelligence. The collective collaboration of multiple humans is one of our superpowers. Ensuring we don’t lose the human perspective opens up much richer analysis in a multitude of ways that we may not have otherwise considered.

Case Study 3: Layered Accountability

Preventative Maintenance Checks and Services (PMCS) is a classic “motor-pool Monday” task within the Army. After first formation, the soldiers and NCOs head to the motor pool and follow the PMCS manual step by step for each vehicle to ensure they are combat ready. At least that’s the intention. In reality, PMCSs are notoriously “pencil whipped”. My first experience was in Korea with my Bradley Fire Support vehicle. Being new, I didn’t know what right looked like and didn’t want to rock the boat. The more I paid attention though, the more I realized that the procedures weren’t being followed and critical steps were being skipped. It all culminated when we barely completed the convoy movement to gunnery. The engine was having issues, the track didn’t handle well, the internal comms didn’t work, and when we went to prep for gunnery, we had missing parts for the M242 25mm "Bushmaster" chain gun. It was a painful learning experience in humility to explain to my leadership why our track was not operational.

Starting the following Monday, I tried to think of how, without myself having to do the entire PMCS myself or standing over my soldiers watching them, I could ensure that all my equipment was up to par. The solution that came recommended by a mentor was insightful: layered accountability. How does one general get ten thousand soldiers to do the right thing all the time? The first step is knowing what right looks like and the second step is finding out the key points to measure.

In the case of my Bradley the solution was nuanced. On Monday mornings, before physical training, I would select from a few options I’d developed, such as:

I’d put a pebble, out of sight, under one of the track’s road wheels. The PMCS requires moving the track to check track tension and brakes. If I came back after the PMCS was done and the rock was still there, I knew they hadn’t completed it to specification.

I would remove the firing pin from the main gun. In this way, the soldiers could not complete the required function check and would have to list it as a deficiency on the PMCS form (or, once they got wise, just ask me for it).

I would cut the lead wires for the fire extinguishers. These were easy to replace but were literally the first check in the manual and if they weren’t repaired, meant they skipped that step.

I would slightly unplug an internal comms cable in different locations. If I checked and it was still unplugged, they hadn’t fully checked the comms.

I had more things that I would measure but the key was that my soldiers did not know which one to look for and so their safest course of action was to complete the entire PMCS per the manual.

The result was that I had vehicles that were in great shape when we went to the field. Furthermore, my soldiers knew that the best way to be successful was to perform to task, condition and standard. I expanded this into layered accountability by creating a hierarchy of measures, based on the Mission Essential Task List (METL) that ensured I could find the key performance measures of my squad leaders and developed related performance measures down to the newest, most junior soldier.

The lessons I learned from that example are that:

Layered accountability ensures multiple eyes on performance indicators that inter-relate to drive large scale performance gains

Sampling critical measures ensures you don’t get into a rut

Making performance visible drives the right behaviors

Shifting from reactive accountability to proactive accountability sets soldiers up for success, not failure, and can save lives.

In application, the key to identifying key performance indicators is to recognize how humans react to metrics.

“Metrics foster process understanding and motivate action to continually improve the way we do business.”5

“What gets measured gets empowered and produced.”6

"Tell me how you measure me, and I will tell you how I will behave.”7 (DTIC, 1991)

Simply put, metrics drive behaviors. If you don’t like the behaviors you see, one of the first things to look at is the metrics you use to measure performance. Many times, this is the solution to the underlying behaviors. In the case of PMCS, the metric was to avoid inoperable vehicles but there was limited accountability for accuracy. Therefore, the behavior was that most vehicles were coded as operational when the truth was often quite different.

Often an analyst can perform simple metrics modeling to identify conflicting, contradictory, and missing metrics that are causing imbalances in the system under measure. This is a crucial analysis to perform when considering Measures of Outcome (MOO), Measures of Effectiveness (MOE) and Measures of Performance (MOP). Furthermore, proactive measures that catch a system before it fails are more valuable than reactive measures that merely point out when a system fails.

Case Study 4: Reducing Risk Increases Danger

This final case study of counterintuitive insights from the war on terror begins on a normal training day in the Army. As is typical with military training, our day at the range for grenade familiarization involve the classic “hurry up and wait.” Soldiers shuffled forward in a line toward the range, entered the protective bunker, received a grenade with shipping safety, quickly moved to a throwing location, removed the safety, pulled the pin, threw the grenade, took cover, and waited for the explosion. Once clear they would quickly exit the throwing location and the next soldier would enter. Everything was flowing smoothly and it was as safe as we could make it.

As we stood around chatting and watching the soldiers shuffle in and out, a Colonel walked up to us and struck up a conversation in that classic manner of a senior leader engaging with junior officers and NCOs. He moved on toward the bunker and after a few minutes, amidst a sudden flurry of activity, came back out with a case of hand grenades and began passing them out to each soldier in line. In short order, all our soldiers were holding live hand grenades and investigating them in ways only soldiers can. The Colonel turned to us leadership and said: “Train as you fight, you’ll be in combat soon, better get used to carrying one of these and not blowing yourselves up. Leaders, you are now responsible to ensure no-one gets hurt.” He then turned and walked away.

Suddenly the relaxed atmosphere evaporated, and all levels of leadership engaged with the soldiers. Quickly, the squad leaders organized their soldiers. Platoon leaders and sergeants organized the squad leaders and made sure that the soldiers understood the gravity of the situation and began instructing on proper carry techniques for live hand grenades. The irony is that this is what we should have been doing all along. We were deploying in a few weeks and each soldier would soon be carrying a myriad of dangerous explosive devices from breaching charges, M203, flash, frag, and smoke grenades, ammunition, and flares. They were also expected to do this in combat scenarios, under fire, and yet we didn’t trust them to hold a live grenade in a rear echelon training event. This was a prime example where the desire for safety could easily increase the danger downrange.

Fundamentally, humans are quite terrible at performing risk assessment. In David Ropeik’s book How Risky Is It Really? this concept is explored by identifying the cognitive shortcuts, heuristics and biases that we use to perform our judgements. He identifies that the removal of risk does not always result in increased safety. In part this is due to the human brain’s coding to maintain homeostasis of good/bad, risky/safe, happy/sad, risk/reward, etc.8 This form of balancing is known as risk compensation,9 where people will adapt their behavior in response to the perceived level of risk by becoming more careful where they sense greater risk and less careful if they feel safer.

This counterintuitive principle is well documented with vehicular traffic where crash speeds increased with seatbelts, tailgating increased with antilock brakes10 and additional studies identified that the safer a work place became, the more catastrophic the injuries.11 It is critical for human factors analysis to recognize and consider these implications when creating solutions for the warfighter.

The lessons I learned from that example are:

Excessive safety measures reduce leader accountability

Risk is a safety measure; when people feel risk, they behave more safely

Safety measures that limit tactical measures don’t win wars

In application these sorts of psychological implications are critical to consider when analyzing Concepts of Operations (CONOPs) and Concepts of Employment (CONEMPs). Recognizing that risk is a crucial input that humans sense and respond to can change the recommendations for design, implementation, and even performance measures. As an example, in Case Study 1, the increased armor and safety equipment on convoys did not reduce the number of IED detonations. Soldiers performed risk compensation and began to rely on technological solutions where, if those solutions hadn’t been available, they would have had to rely on tactical solutions.

Conclusion

Ender’s Game is a book that transformed how I thought about problems. The ability to shift perspectives, reframe, challenge assumptions, and think beyond the established paradigms provided multiple, counter-intuitive successes in my career. I have applied these insights to the profession of operations research in the fields of autonomy, artificial intelligence, human/machine symbiosis, cyberspace, and technology enabled future warfighting concepts. My goal is to show how anyone can benefit from these lessons and apply them to their analysis, leadership, and projects.

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Woudenberg, M., & et. al. (2017, September 11-14). Concept of Operations for Test Cost Analytics Teams in Complex Manufacturing Environments. IEEE AutoTestCon Conference. Schaumburg, IL, USA: IEEE.

United States Army. (1969). Improvised Munitions Handbook TM 31-210

United States Army. (2011). Ranger Handbook SH 21-76.

Ward, D. (2014). F.I.R.E. – How Fast, Inexpensive, Restrained, and Elegant Methods Ignite Innovation. Harper Business.

Belasco, J. A. (1991). Teaching the Elephant to Dance: The Manager's Guide to Empowering Change. Plume.

Goldratt, E. M. (1990). The Haystack Syndrome. Croton-on-Hudson: North River Press, Inc.

DTIC. (1991). The Metric Handbook AD-A248 591. Defense Technical Information Center.

Levari, D. E., Gilberg, D. T., Wilson, T. D., Sievers, B., Amodio, D. M., & Wheatley, T. (2018). Prevalence-induced concept change in human judgment. Science Vol. 360, Issue 6396, 1465-1467.

Rudin-Brown, & Jamson. (2013). Behavioural Adaptation and Road Safety: Theory, Evidence and Action. CRC Press, 67.

Vrolix, K. (2006). Behavioural Adaptation, Risk Compensation, Risk Homeostasis and Moral Hazard in Traffic Safety. Diepenbeek: University of Hasselt.

Hedlund, J. (2000). Risky business: safety regulations, risk compensation, and individual behavior. Injury Prevention.

Case Study #3: I trolled my boys until they got wise to my shitposting.