Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic probes the trend of so much of our communications moving from voice to text. We’ll look at the patterns, the psychology of data ingestion, common pitfalls of text communications, and recommend some key opportunities to avoid the Con[of]text and ensure true context.

We are imperfect humans, using imprecise language, to communicate incomplete ideas.

The recent boom in remote and hybrid work really highlighted that when we remove the rich context of in-person communications, we lose the signals, inflections, and intentions that can be more readily transmitted. It forces a more nuanced approach to our work environments and requires a lot of additional attention.

Yet paradoxically we also see a burgeoning of anti-voice communications with online memes like:

“Before you call me, always ask yourself..is this textable? And if it is, you TEXT. And if you don’t, I will cut you.”

When we resort to text, we reduce a significant amount of context, we are often distracted with other information, we lose meaning, we respond quickly and we fail to recognize both the human in us, as well as the human on the other screen. The intentional separation of our communications into highly misinterpretable bits has been linked to the high rise in teen and young adult anxiety, depression, and suicide. It’s not well adapted to how our brains are coded to interpret the world around us.

Psychology of Content Ingestion:

Our brain has two job duties:

Make sense of the world around us.

Be computationally efficient.

To balance these two requirements, our brains apply over 200 listed Cognitive Biases in four groupings: How to handle a lack of meaning, too much information, the need to act fast, and knowing what to remember. Humans do well with small amounts of good information. However, the more data, with less meaning, the more biases are applied for sensemaking, which leads to conceptualizations of the world that tend toward edge cases, not the center.

I deal with these edge cases daily while working in AI design as we apply cognitive science to mathematical computations. The more assumptions or heuristics that are applied to an algorithm, the faster it moves toward the edges of the data. The same goes for human interpretation of text-based communications.

A great example is Twitter. It provides too much information, in short bits without enough meaning, and drives the need to act fast to trend. Fundamentally this is the issue with text-based communications. It often triggers stacked biases, especially when the information might challenge existing biases on emotionally charged topics. These stacked biases often manifest in interpretation, that is, how my words sound when you read them is a majority function of what’s in your head!

It’s not what I said, it’s how you read it!

Once my words leave my head and enter the text, I can only hope that my tone and tenor convey the right meaning. This is why I use textual analysis tools in these essays such as Grammarly to see if my tone is optimistic, pessimistic, open, playful, closed, etc. Yet I can only control it so much. This is why I like recording voice-overs. If you’ve ever wondered how these essays sound to me, I recommend you listen to me read them. (see these podcast players)

This highlights why it is so important to be highly cognizant of the voice in which you read things. Especially on challenging or contentious topics. COVID became a great case study in communication as social media was infested with debates and arguments about the virus, the protocols, and then black lives matter and the election. Let’s just say that was a year when the problems with text-based communications became clear, especially since so many people didn’t engage face-to-face anymore with the lockdowns.

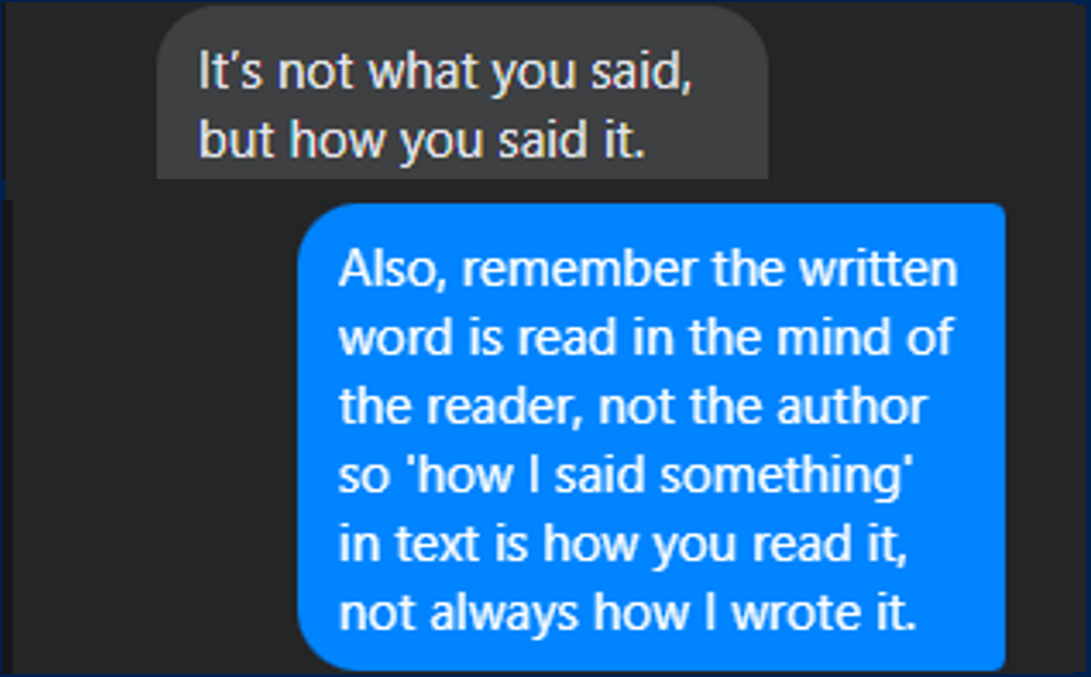

After one engagement on Facebook, a friend reached out in Messenger and provided feedback regarding a discussion where, among other things, they stated “It's not what you said, but how you said it." To which I responded, " Also, remember the written word is read in the mind of the reader, not the author so ‘how I said something' in text is how you read it, not always how I wrote it. “

What emerged was that, if you agreed with my positions, I sounded rational and composed. If you disagreed, I sounded foolish and unhinged. At one point, in late 2020, I was out in person with a group that contained both types of people. We were engaging in a similar discussion topic to what we had online and the conversation was so much better! In fact, one of the people who often disagreed with me made the insightful comment:

“You sound so much more reasonable and thoughtful in person”

To which I responded:

“The way I talked just now is how I always sound in my head when I type. How do I sound in your head when you read it?”

Their response:

“I’d never considered that!”

I applied these insights recently to a disagreement two co-workers were having. Each was complaining about the other’s rudeness, unprofessionalism, and tone in IMs and e-mails. Curious to explore my ideas about how we read each other’s words, I asked them each to do two things based on a specific e-mail thread:

I had them read their e-mails to the other in the voice they intended

I had them read the other’s response in the voice they interpreted.

I recorded them reading and then exchanged recordings. The result was fascinating:

At first, there was indignation at how they were interpreted.

Then there was the recognition of what they had recorded.

And then the resignation of what had really happened.

I brought them back together and then shared the mix of both of their interpretations which sounded nasty and spiteful. Then I shared the mix of both of their intentions and they sounded kind and reasonable.

It was a really interesting experiment because it didn’t have nearly as much to do with what they said but how each interpreted them as saying. Again, how you heard the other person say it in the text is more often actually only in your brain and may not reflect their intent.

One time, I had a leader who absolutely refused to accept there could be a different interpretation than what they had. They did not have the good faith to even consider the two-way street of communication. For example:

On voice calls, they were clearly multitasking or not open to discussion.

They grossly misinterpreted feedback from others and upon correction, doubled down.

They stated that Instant Messages were “intrusive.”

The entire team was told that e-mails over 3 lines would not be read

But with every truncation, they lost context, and lost context opened up misinterpretation

In-person wasn’t much better as I was told asking for the ‘Why’ was disruptive.

While we have a textbook recipe for ‘what not to do as a leader’ the most interesting aspect was enlisting the help of my wife to craft responses. I’d literally have her read the communications and phrase a response that I, personally, wouldn’t have thought of. The result? The feedback was that my tone was still a problem or some other negative interpretation. It literally wasn’t even something I said, nor ever how I’d say it, and it was still interpreted as such. I even enlisted the help of others to coach my in-person and voice comms. It just highlighted that when a person is set to an interpretation, it’s really hard to shift it.

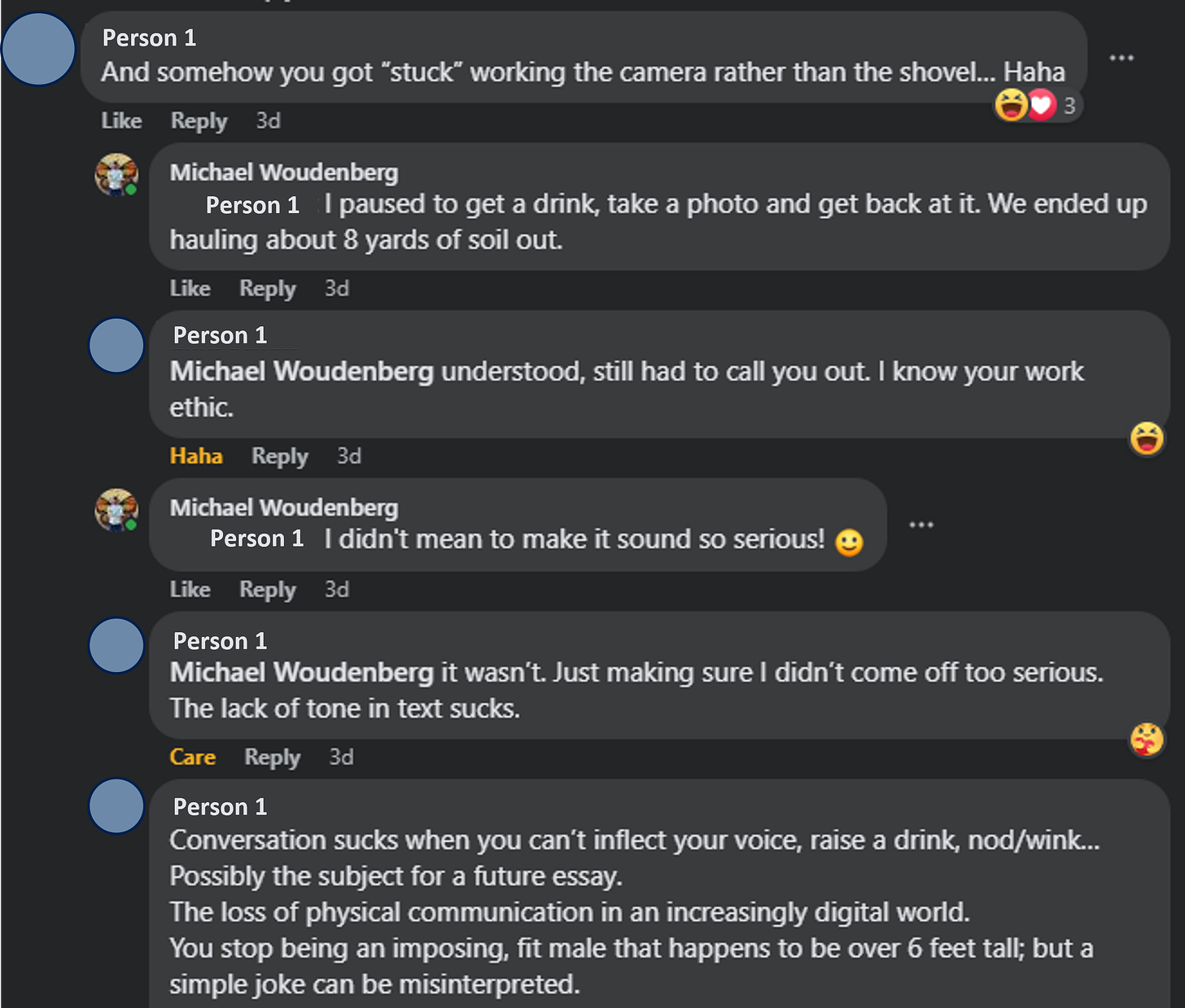

These problems also emerge with the most innocuous exchanges, between two very good friends with zero negativity. This Facebook exchange below is a great example. What’s weird is that I didn’t take any offense to it, yet there was a way in which my response could be interpreted. And this person is right, there is a lack of tone in text that we fill in with our own brains.

What to do about it?

Fundamentally, an adage that I’ve found so true on so many interpersonal topics comes to bear:

You expect from others what you expect from yourself.

Whose voice is that in your head? First off it’s your voice. Second, if it sounds mean, look inside first. Strip off as much of your layered biases as you can. Try to put it in context. It’s like that great statement from the Bible’s New Testament

“Why do you see the speck that is in your brother's eye, but don't consider the beam that is in your own eye?”

Between these two ideas, much of our communication issues can be resolved by focusing on ourselves first. There’s an old marriage adage that says “If there are two ways to interpret something and one of them offends you, assume it’s the other.” Because it really is just a voice in your head 99% of the time.

Another aspect is to turn toward more voice conversations or a blend in between. Try to use the same words and phrases in both settings. I like to reference text-based communications in my verbal engagement in the tone I intended, especially if they could be, or were misinterpreted:

“Like I said in the e-mail, I do think it’s a great idea and I’m wondering if we’ve done XYZ analysis to confirm?”

This last example was one I had where someone complained that I was criticizing the idea because I asked if we’d done that analysis. I don’t know the tone they ‘heard’ but I was able to place my tone on the question in a meeting the next day and it resulted in a much better conversation.

I also recommend that you keep a consistent tone between all communication mediums to maintain a common profile. This has proven useful for me where coworkers have been able to provide correction to a misinterpretation from others. We’ve all heard the “that doesn’t sound like something [this person] would say”

A last recommendation is built on a similar function I use in person and I’ve learned to use it in text. As the Facebook conversation above captured, I’m a 6’6” 220lb athletic former Army Ranger with a booming voice, a polymathic breadth, and a gregarious personality. A mentor of mine once recommended that I caveat statements with qualifiers such as:

“I’m really passionate about this, and I don’t know a better way to say this”

“This is a tough subject, and I don’t have a polished response, so work with me as I try to articulate it”

“I’m not sure I undersand your question, here’s what I think you said and here’s my answer”

“I’m speaking frankly here”

“I worry that this might be interpreted wrong so let me specify my intent”

I’ve found these work well both in person and in text in allowing the reader to reframe their interpretation. It still doesn’t allow you to fully control the interpretation. I’ve still had two people walk away from the exact same conversation with completely different interpretations.

A last thought is the use of the ‘smiley face’ emojis. These can be a mixed bag but they can add a playful aspect to the communications. I find they work best if you use the happy ones, and use them to make fun of yourself, not others. This isn’t a silver bullet but is part of a whole awareness of the situation

Conclusion:

Text-based communication loses context. The increased push toward more texting and away from voice communication is a problem in my mind as it inevitably leads to misinterpretation. But an understanding of the problems and an application of the solutions do make things a lot better. Specifically, if you recognize the interpretation is in your head.

It is possible to have highly productive conversations in text and it requires both sides to assume positive intentions. Should you find yourself at odds with another person, look inward first, and then try not to take offense while gently explaining your intent to the other. Remember, sometimes it’s best to just pick up the phone, apologize for the situation, and try to clarify. And it is also best to answer the phone, and listen in return! This was a major lesson my wife and I learned as we tripped over all of these challenges over 3.5 years while dating and early marriage when I was in the Army and we were on separate continents. The key was recognizing we were in it together and had positive intent.

We are imperfect humans, using imprecise language, to communicate incomplete ideas. Grace, humbleness, and forgiveness in all dimensions are crucial to weaving successful communication.

We are imperfect humans, using imprecise language, to communicate incomplete ideas.

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further Reading from Authors I really appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares

Looking for other great newsletters and blogs? Try The Sample

Every morning, The Sample sends you an article from a blog or newsletter that matches up with your interests. When you get one you like, you can subscribe to the writer with one click. Sign up here.

Also, if you have a newsletter you would like to promote, they offer a great service that gets your writing out there to a new audience.

Your brain is designed to move your body in order to perpetuate life. Your pre frontal cortex can contemplate communication.

Michael I just read your latest post about art and AI. The first image of this post, with two people looking at screens but facing opposite directions, is a great example of your argument! Without generative AI, I guess you would either have skipped putting an image altogether, or lifted one from a google image search. Generative AI has enriched your post.