Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic is another collaboration with

and delves into what we call Critical Thinking and, in doing so, uncover the core of Polymathic Disciplines captured as the ability to “Learn, Unlearn, and Relearn.” We’ll contextualize the push for, and against Critical Thinking and dive into what we really mean with these two words.To many of us, the topic of critical thinking is nearly a trope; a simple concept we think we do and certainly expect others to do. As such, the ongoing debate in the field of education between knowledge and skills passes us by unawares. It’s only when articles such as Thinking Critically About Critical Thinking, There Is No Such Thing as "White" Math or Is music theory really #SoWhite? appear in our news feed that we begin to wonder what on earth is happening in the world. The attacks on critical thinking hinge on a hypothesis that it is not a teachable skill or worse, that it’s a function of a biased power dynamic.

While might seem patently absurd, the root of the problem is in the fact that few people have ever paused to consider what those two ‘simple’ words mean; Critical + Thinking.

Therefore, it becomes necessary to investigate critical thinking and break down the concept into three skills: managing knowledge, structuring logic, and applying critique. When we first dove into this over two years ago, we didn’t expect that we’d be uncovering the core of Polymathic Disciplines and crafting a framework that anyone can use.

I Think Therefore I Am

The concept of critical thinking breaks down into two functions: thinking, which we will address now, and critique which we will address next.

Thinking nicely divides into two main functions: managing knowledge and structuring logic. In this view, it is essential to discern what knowledge is required for thinking: Explicit expertise is not required to perform critical thinking as much as appropriate knowledge.

One doesn’t need to be an expert in epidemiology to be able to think critically about COVID-19; however, one does need a network of navigable knowledge across psychology, virology, immunology, and sociology. In short, one of the strengths of the Polymath.

A crucial skill at the heart of knowledge management is knowing when enough information has been gathered to analyze a particular problem and the ability to determine when a degree of expertise is or is not needed.

Great examples of this are elementary school math word problems which provide more knowledge than is required to solve the problem and the extra information distracts from the correct answer. It is crucial to be able to determine when more information does not improve the analysis and to know when you need to expand the analysis to include other information outside the scope of the explicit discipline.

The second tenet of thinking is logic. Consider the following definition from Introduction to Logic 3rd Edition:

“Logic is the analysis and appraisal of arguments.”

As such, logic provides the structures to compose and decompose an argument. As further defined in the textbook:

“A good argument not only possesses validity and soundness (or strength, in induction), but it also avoids circular dependencies, is clearly stated, relevant, and consistent; otherwise, it is useless for reasoning and persuasion and is classified as a fallacy.”

Logic allows us to avoid analysis pitfalls. Most of us are familiar with the logical fallacies of ad hominems and appeals to emotion, tradition, novelty, and experts. In our hurried attempts to crush the proposed arguments of others, we often fall victim to committing formal and informal fallacies.

This logical structure also helps us avoid biases in data and analysis as we’ve covered previously in Eliminating Bias in AI/ML by having clearly defined requirements, expectations, and the ability to see if your knowledge is appropriately complete. Structured logic avoids these pitfalls and provides the ability to group, ungroup, regroup, and order the knowledge that has been collected.

Combining Logic and Managing Knowledge into thinking creates the ability to form, un-form, and reform ideas logically with the appropriate information,

Is Everyone a Critic?

Now that we’ve established thinking as the ability to form, un-form, and reform ideas logically with the appropriate information, we turn to explore what is meant by “critical”.

With the onslaught of social media platforms, it appears that everyone’s a critic! However, a critic, from Greek krites, was a judge or umpire, valued for making informed decisions. Being a critic is more than an ability to mindlessly bludgeon an idea and lynch anyone caught in disagreement. Instead, a critic should be one who can provide a rational, skeptical, and unbiased analysis.

To be a true critic requires mindfulness, that is, the ability to identify, sort, and challenge internal and external assumptions. A heuristic developed by us captures this succinctly:

“Everyone is biased—the key is knowing what yours are.”

This crucial step invites everyone to consciously and purposefully pause and acknowledge the perceptual landscape being considered. In other words, there is more than one perspective and by understanding the scope and limitations of your own, you can begin to see the perspectives of others.

A key element is to recognize that we Know Nothing, and are susceptible to the two key cognitive biases of the Dunning-Kruger Effect and Cognitive Dissonance. When we’ve mastered these two, we can begin to explore more.

An easy way to think about how different perspectives lead to a partial understanding of the whole is in the tale of the blind men and an elephant which was captured in 500 BCE. Ancient wisdom recognized the need for awareness of the perspectives, and it remains as true today.

Criticizing or challenging assumptions can be easy. Understanding why they exist is far more difficult. We see this with social justice warriors challenging all manner of social structures. All too often, their clawing for influence materializes as little more than repeatable soundbites for their social media followers. They are lauded as informed critics yet lack a mindful perspective, giving rise to a general trend we are all liable to slip into; challenging to destroy, not to understand.

In response, one key function of mindful critique is to apply Chesterton’s Fence:

“In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, ‘I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.’ To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: ‘If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Lastly, being a critic leverages curiosity as a powerful booster where different viewpoints are investigated, knowledge is explored, and ideas, even bad ideas, are considered with a passion to understand and question. This is the underlying foundation of Systems Thinking.

A true critic requires curiosity and the ability to be resilient and willing to challenge their own perspectives and biases. In this manner, we can avoid strawman fallacies and, instead, can steelman the other perspectives before we attempt to argue against them. Mindfulness is a skill and curiosity is a feature of being a critic and both are essential to critical thinking.

The Trifecta Analyzed

The knowledge, logic, and critique trifecta are like the three legs of a stool where removing one of the three causes the stool to fall. Let’s consider a few two-legged stools:

Knowledge and critique without logic can be a crusader. Lacking logic, a thinker will tend to validate a narrower focus of perspective and suffer from confirmation bias with knowledge.

Critique and logic without knowledge are sophisticated ignorance. An ability to identify assumptions and construct logical conclusions without the depth of knowledge is shallow.

Knowledge and logic without critique is dogmatism. These are often the experts for which Planck’s Principle is paraphrased as: “Science progresses one funeral at a time.” Their inability to challenge internal and external assumptions insulates them from truly transformative critical thinking.

With this foundation established on the skills involved in critical thinking, we can focus on applying these concepts to a couple of simple examples.

Application of Critical Thinking

The first step in applying critical thinking is recognizing the scale of the application. Both of us authors have spent time applying this construct in the work we perform analyzing complex geopolitics to apply cutting-edge technologies. We use the trifecta on artificial intelligence, machine learning, and modeling and simulation. The complexity of these analyses is challenging to junior analysts we work with because of their limited knowledge on a broad range of topics.

So, does that mean only experienced analysts can think critically? Far from it. We teach everyone the skills of knowledge gathering, problem scoping into digestible parts, applying logic, and the application of critique to invite, consider and capture different perspectives. These skills also decompose from adult learning down into high school and elementary education.

Joshua spent twelve years instructing high school and college mathematics, breaking down complex concepts and then building them into more abstract mathematical theories. Teaching math to children and teens required applying our proposed critical thinking skills. In both education and research and development, he takes discrete knowledge, applies logic to form, unform, and reform mathematical concepts, and critiques these advanced formulas to ensure both verification (logically correct and applied to the correct perspective) and validation (ensuring the best application to solving the question).

Michael has spent over sixteen years training, coaching, and mentoring teens and adults in data analytics, process analysis, and logical deduction. His work in applying cognitive science to autonomous systems was crucial to formulating this proposed concept of critical thinking. On a personal level, he has also applied the trifecta approach to teaching his children chess. Here he teaches the knowledge of chess such as the pieces, the movements, the structure, and the history. Then he has them apply logic in forming, unforming, and reforming strategy. Finally, critique is instructed to analyze the ideas they have formulated against how they can perceive their opponent’s tactics and logic, and attempt to discern their strategy. It has been rewarding to see them apply critical thinking, at this scale, to dramatically improve their gameplay though they lack years of knowledge-gathering experience.

Finally, it should be noted that this concept borrows extensively from classical education where, according to the trivium, grammar, and rhetoric serve alongside logic as three of the seven liberal arts. Schools throughout history viewed a pairing of appropriate knowledge with logic to be foundational to the application of critique.

The Risks of a False Dichotomy

The ongoing debate between knowledge and skills in the field of education is a false dichotomy. Applying our critical thinking skills to the debate identifies more than just skills or knowledge.

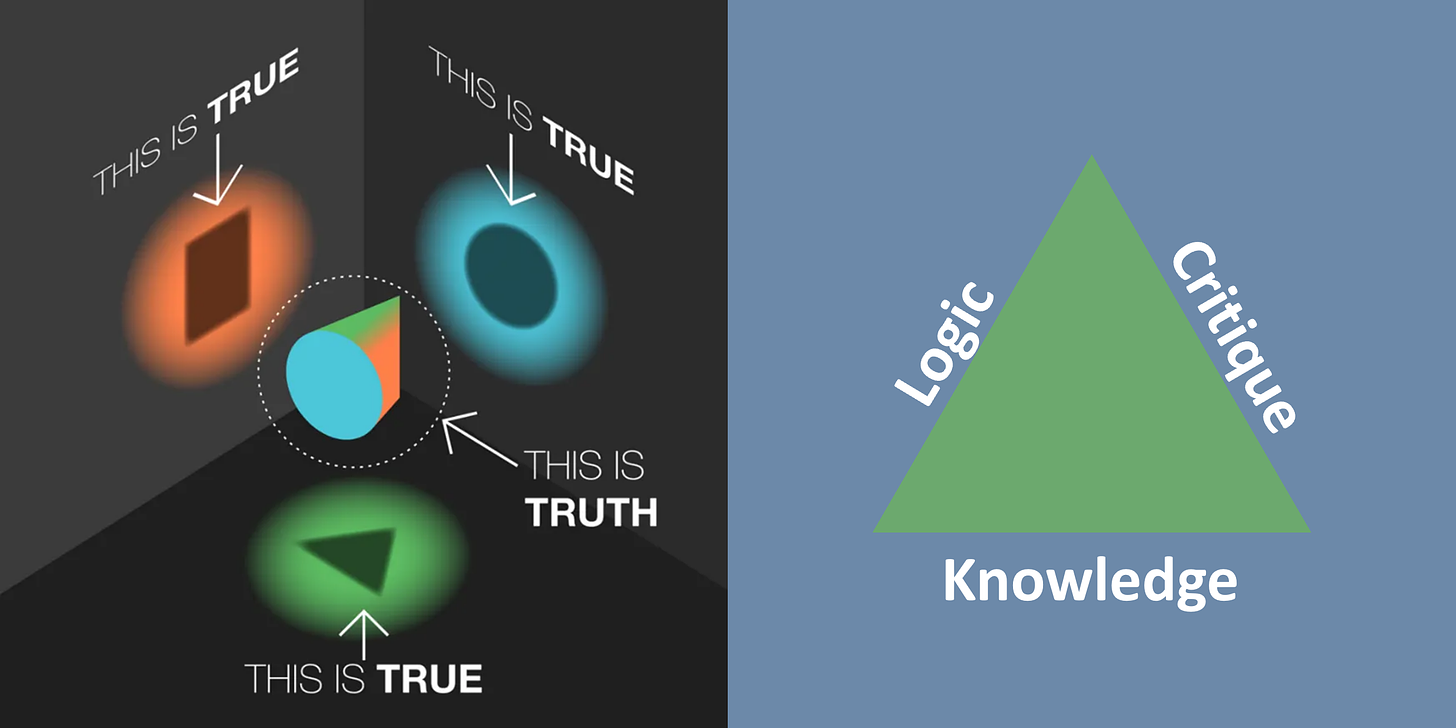

Take the image in the meme below. All three perspectives are correct. Yet they are all incomplete. Ironically, the true shape in the meme below is a wedge and that is exactly what is dividing the two sides of the debate.

Instead, we propose that education should be a balancing and tailoring of skills and knowledge. This is akin to the third perspective of the equilateral triangle where logic and critique are the skills added to complement a balanced acquisition of knowledge, thus forming the three sides of the triangle, revealing our trifecta. If you ignore the triangle, you fail to recognize the perspective that articulates the wedge, thus perpetuating many disagreements.

Our primary concern, emanating from the false dichotomy, and what is driving much of the polarizing headlines, is the suggestion that knowledge, and primarily knowledge, is the solution for education. This idea that we can pour knowledge into students, employees, or leaders and they will absorb it like a sponge, and with that knowledge, critical thinking can naturally occur is just not true.

Worse, it has led to much of the political polarization, wrongly applied science, and poor risk and opportunity management we see lamented in many of the articles on the topic. The reason this hypothesis fails is that our brains have over 200 titled cognitive biases loosely categorized as applying to manage too much information, not enough meaning, the need to act fast, and deciding what to remember.

These biases work well on structured information but fail when applied to large volumes of less organized information. To process large volumes, we resort to stacking multiple biases to ease the cognitive load which often leads to a concocted edge case. Our personal experience applying cognitive science to artificial intelligence and machine learning is teaching us this lesson where more data (knowledge) can lead to very inaccurate results.

Claire Lehmann, from Quillette, also captures this risk very well in Stop Calling People “Low Information Voters” where she suggests that:

“… ’high information’ people are not immune to irrationality. They are just as likely to be ideologues who are resistant to updating their beliefs when faced with new evidence. This includes social scientists.”

This also includes every discipline where experts need to recognize that irrationality is not mitigated with knowledge, but that knowledge needs to be paired with logic to establish structure and with critique to identify and manage biases to avoid polarizing edge cases.

Critical Thinking Summary

The future is ours to define and we certainly don’t need to cede our educational systems to the latest vogue philosophy. With this simple framework of critical thinking, we can design our educational systems to avoid the false dichotomy.

Studies can be focused on teaching the skills of knowledge gathering. Curricula can emphasize skills in logical composition and decomposition of ideas maturing from simple to wicked problems where answers become better/worse, not right/wrong. Lastly, education can teach the skills of the critic where the identification, analysis, and challenging of assumptions can occur.

Knowledge gathering, application of logic, and mindful, curious critique are all skills that can be learned and refined through exposure, experience, and discipline to where they become an underpinning of Systems Thinking. It isn’t a square and it isn’t a circle, it is something much more useful.

This trifecta of critical thinking captures what Alvin Toffler paraphrases as

“…by instructing students how to learn, unlearn and relearn a powerful new dimension can be added to education.”

We believe that the necessary tools to analyze the world are the skills of critical thinking comprising structured knowledge, logic, and critique. This simple application can be applied in a structured curriculum to leverage powerful ideas and allowing our future generations to continue to grow.

Annual subscriptions for 20% off!

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further Reading from Authors I really appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares

Love the observation on how maturity plays a role in how we think. It’s easy to forget that our brains grow and change over our lifetimes, molding to new patterns of thinking that we rehearse. Therefore, it is vital that we choose to establish the neural pathways which lead to critical thinking as opposed to just going with the flow of others or doing what we’re told by institutions.

Happy to have discovered your Substack Michael. Thinking about letting my 12-year-old read it too (when I asked her what she wants to be when she grows up, she said “I want to be a polymath.” Funny - she already is! Exhibiting artist, singer, plays 3 instruments, loves math and writes at high school level).

On the ability to think critically and with nuance. This is an ability we are losing fast, ironically due in large part to the way we approach and use technology. Technology that has such profound potential, and humans are blowing it a little. This is the reason I’ve joined Substack in fact. To do my part in fomenting nuanced thinking in society. And to find others doing so.