Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and explore them from different perspectives and disciplines, to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic is a psychological exploration into a few of our cognitive biases and how they cause us to see the world as significantly worse than it really is. Not just worse but with the dismal outlook that we are facing an apocalypse. This outlook is tightly coupled with a nostalgic yearning for how things used to be. Let’s explore what drives this and rewire our perceptions to understand why we always see an apocalypse.

Intro

“Things have never been worse!”

“The world’s so much more dangerous!”

“Politics have never been more divisive.”1

I’m sure we’ve all heard something along these lines, particularly if you live in the US. I find the statements fascinating because they’re intoxicating. They grab our attention and pull us in fueling social media outrage, pontification, and yearning for yesteryear.

Recently there was a post from a fellow I appreciate,

which dabbled in this topic area. Here’s a quote that I found interesting:There was a time, you can remember it you think, when the streets were clean, everywhere wasn’t covered in litter and local councils made it their business to make the place bright, cheerful and pretty. Perhaps it is nostalgia but wasn’t there a lot less crime and didn’t you used to know the name of the local policeman?

There are a ton of layers here to tease apart. In reality, he’s describing my hometown circa 1995. He’s also describing my college town in 2005. He’s also describing thousands of rural towns and close communities around the world today.

Here in Tucson, I can drive across town and generally see clean streets, I see happy people and smiles, I see polite nods. Then I go online or watch the news and a much different and darker picture emerges. Which view is true though? Let’s take a look around at what we do have today.

Data Analysis

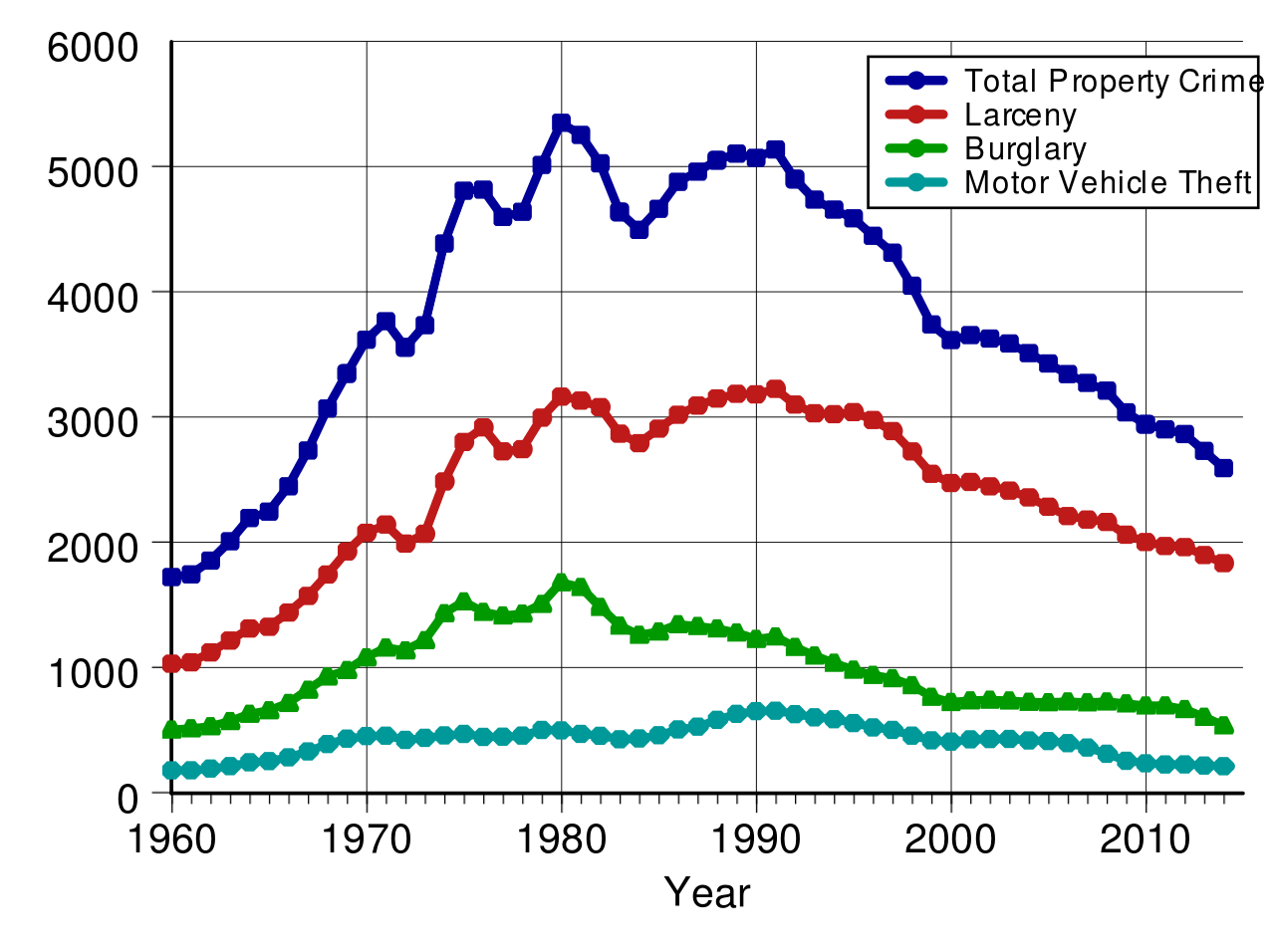

Crime of almost all types is lower (only recently has there been a small surge)

Crimes against Children are also way down where, from 1990 to 2007, substantiated cases of child sexual abuse have declined 53%, and physical abuse substantiations have declined 52%.

From 1993 to 2005, sexual assaults on teenagers decreased by 52%. The subgroup of assaults by known persons decreased even more dramatically.

Other crimes against children 12 to 17 years old have also declined: Aggravated assault down 69%, Simple assault down 59%, Robbery down 62%, Larceny down 54%

To find a similar level of crime we have to go back 60 years. That’s quite a long haul and reflects the teenage years of our elderly boomer generation. It’s also skipping over 1975-1995 which was horrible on almost all dimensions so let’s go ahead and use 1950-1970 as the period that seems to be in scope for nostalgia. I think that’s what’s described by one gentleman in reply to my question about whether that time was better than now:

You’re jaded - you don’t remember a Time Before. You think its mythical - but us, we’re speed running the last 60 years and can see the decline clearer than you can

On first analysis, I think that period is a bit too generous because it is bookended by the Korean War and the start of the Vietnam War which, together, claimed over 100,000 American lives. Then add in the race riots, assassinations, war protests, civil rights marches, and general discontent that festered in the 1960s and we need to narrow down our nostalgic window to 1955 to 1965.2

That decade had a similar level of crime as now, but what about the standard of living? Let’s compare starter homes. In 1955, for $8,000, you could get a 955-square-foot house, with no TV, no garage, a tiny fridge, no microwave, no air conditioning, linoleum flooring, and limited insulation.

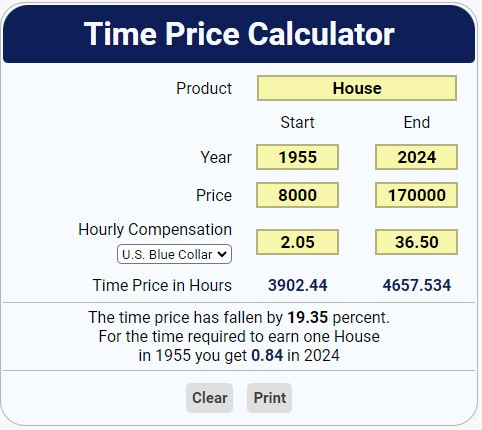

But they were cheap, right? Only $85K in inflation-adjusted dollars. Let’s compare that to a starter home today which runs $170,000.3 That’ll get you about 1500 - 1800 square feet, modern appliances, air conditioning, high-speed internet, tile floors, and improved energy efficiency for lower utility costs.

It’s still twice the price so let’s deepen the analysis using a time price calculator created by

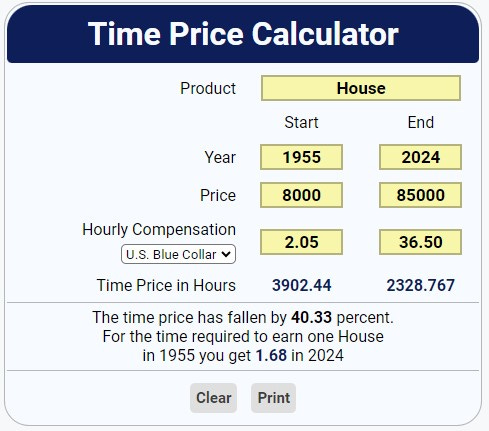

. This measures the number of hours it takes to pay for an equivalent asset. We’ll analyze the houses against a standard blue-collar job.If you bought the identical 1955 house, inflation-adjusted, but at today’s wages, it would take 40% fewer work hours to pay for it (Picture 1)

However, our modern starter home is twice as big, much nicer, and more expensive. But with the wage increase, it only takes 20% more effort. (Picture 2)

Let’s look at food next, I’m going to pull an example from 1947 because it was highlighted in a recent series of posts online and in a Life Magazine article “1947 Heroine of the Battle of the Budget” featuring Ann Cox Williams who is lauded for feeding a family of four and her cat for just $12.50 a week! How’d she do it?

Inflation-adjusted, that $12.50 becomes $176.05 per week today or $700 / month

She serves no meat at lunch and limits her evening entrees to meatloaf, hamburgers, and chili.

She does have two desserts daily and frills like cookies for a party.

She feeds only herself, her husband, and four-year-old twins.

She shops sales and clips coupons.

My food budget today is also $700 / month and I guarantee I’m eating much fresher, and higher quality food than she’s showing there. I feed an older family of five and we eat meat at every meal. We do shop sales and never pay full price for meat. Even crazier, the Time Price Calculator shows that $12.50 in 1947 would have taken 9.6 blue-collar labor hours. Today, it would only take 4.8 hours to earn that same money.

That decade of nostalgia, that ‘mythical Time Before’ doesn’t sound nearly as great. But for those living through it, it was the best time because they were coming out of the trauma of World War 1, the Great Depression, World War II, the Korean War, and finally things had settled down. It was also the height of technology and medicine benefiting from advances during World War II.

How does that compare to today? Our crime rates are back to the same, we’ve just exited two wars. Our neighborhoods are clean, we have homeowners associations holding standards, the EPA has cleaned up tons of pollution and the environment is healthier than the 1960s. Even more so, our standard of living is unfathomable to those 60 years ago. Those below the poverty line today live better than that blue-collar family in the 1960s. So why do we think it’s so much worse?

The Psychology

Our brains are wired for survival. Currently, we are alive. That means we survived everything in the past. We likely survived very dangerous things like war, car accidents, and more. But it doesn’t help us to remember all that and we don’t need to carry that trauma forward so our brains remember pleasant things more accurately than unpleasant ones. It’s called the Pollyanna Principle.

This builds into a concept I call nostalgia bias. This is where a period in our formative years just sticks in our memory. It’s why we like the music of high school and college more than now. It’s why so many popular kids move back to their hometowns to relive their glory days. These times were formative and fondly remembered.

The past can’t kill you, but the future certainly can. Negativity bias manifests here where we over-emphasize the future negative and under-emphasize the positive. It makes sense because a negative can kill you while a positive can only make life better for a short while. Focusing on the negative and preparing for worse things to come is, and was, a successful evolutionary tactic.

Nostalgia and negativity bias means the best of times are always behind you and the worst can only be up front. It’s a paradigm I explore in my first novel Paradox with the addition of a measurement bias that complicates everything even more:

“Yet everyone thinks the world is going to hell.”

“It’s a really odd human condition. The apocalypse is always right in front of us.” Alex frowned. “Almost all the religious prophets have been wrong about the end of times they predicted. We are so coded for negativity bias that it completely blinds us to what is actually going on.”

“Don’t forget homeostasis,” Kira added. “The purple dot problem.”

The Purple Dot Problem was an experiment conducted by scientists from Harvard, Dartmouth, and New York University that presented participants with a simple test. Determine whether the dots were blue or purple. For the first 200 tests, everyone was shown an equal number of blue and purple dots, and the subjects were accurate.

Then they started to remove the blue dots until it was almost completely purple. counterintuitively, the answers got increasingly less accurate with participants measuring shades of purple as blue, maintaining an equilibrium of colors.

The experiment extended into providing positive and negative scenarios. As fewer clear negatives were presented, more positives tipped into negatives. We see the same thing today with the reduction of overt racism being replaced by microaggressions and people still claiming that racism is as bad, or worse than ever.

Our world is quantifiably better than it was at any point in time in human history, for analogy, it’s more purple. Evolution has coded us for negativity bias because bad things can kill us so even though there are more good (purple) things, we begin to shift them to maintain a homeostasis with the bad (blue).

We also accelerate the Purple Dot Problem with availability bias. You don’t have any murders in your town? Not to worry, CNN will show you every murder in the US. No murders in the US? I’m sure there’s a travesty happening in Africa that Fox News can show tonight.

News goes by an adage, “If it bleeds, it leads.” We now sample that blood from across the planet. It’s no wonder we have a wonky perception and then nostalgically long for the past.

Path Forward

As has become a bit of a mantra here on Polymathic Being, the first step is to realize we are biasing our perceptions of the world. Only then can we intentionally pivot and step away from the mechanisms feeding us a non-stop deluge of negative information.

Next, intentionally start adding new information sources to replace our media diet of what can only be called outrage/fear porn. One of the easiest to check out is

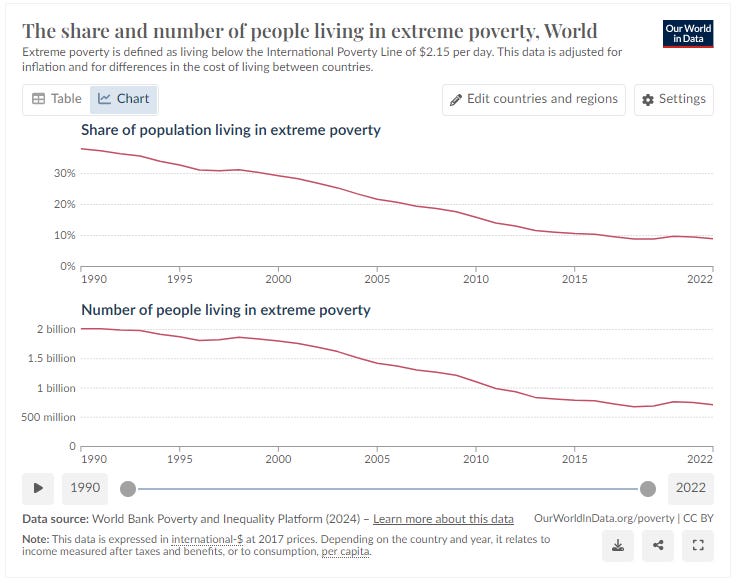

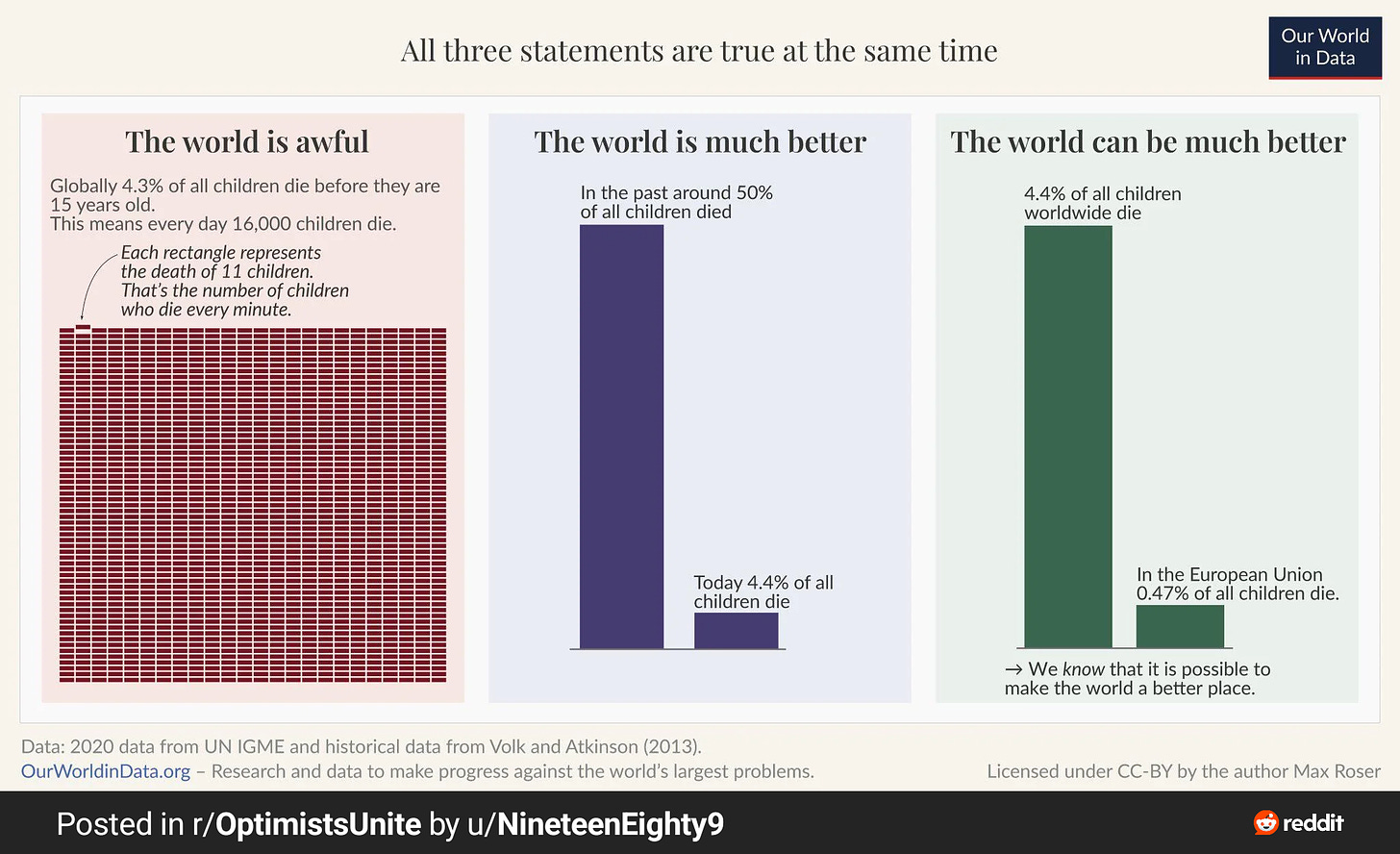

writing . He covers tech and future-looking trends that can lead to human flourishing. Also, check out where he offers a Weekly Dose of Optimism.Another way is to go to Our World in Data where some of our data came from today. They cover topics across every conceivable measure of human existence and the story remains the same; we live in the best of times as this chart shows with global poverty being cut in half in just under 20 years:

I also recommend the book by Steven Pinker titled Enlightenment Now. It’s chock full of data showing how things have gotten better, and dramatically so, across all demographics and countries over the past centuries. It’s sobering in that it highlights just how wonky our perception of the world really is.

Lastly, it helps to remember that we aren’t the first generation to suffer from this wonky perception. History is replete with the writings of influential people who could be copied and pasted next to descriptions of today. We’ve been paranoid about politics, conspiracies, technology, and the destruction of the social fabric throughout all of time. Take this article from 1964, that ‘mythical Time Before,’ which reads as if it were talking about politics today. Yet here we are, 60 years later, and while our politics and society sound the same, a lot more has dramatically improved.

In the past we had the same fears, the same anxiety, the same nostalgia for a mythical time before. Yet we survived, we advanced, we improved, we learned, we got better, and with a simple reframing, we can keep that pattern going long into the future.

For fun, I’ve appended the full excerpt from Paradox: Book One of the Singularity Chronicles where Kira and her friend Alex wrangle the complexities of the purple dot problem and the counterintuitive nature of progress. It’s from Chapter 9: Hope for the Future: (grabbing a copy of Paradox for just $1 gives me hope for the future too! 😀)

This will be trimmed in most e-mails so click through to keep reading.

“How’s Brad?” Brad and Alex had met in college and they’d been married now for five years.

“He’s good, He’s in Africa right now helping set up a school.”

“Oh really? That sounds like a lot of fun. How’s that going?”

“Africa has come a long way.” Alex continued, “Thirty years ago there was such a divide between boys and girls and now that’s basically closed. Poverty was cut in half in under twenty years. They went from only twenty percent having access to clean water to over ninety percent. The change is incredible.”

“Yet everyone thinks the world is going to hell.”

“It’s a really odd human condition. The apocalypse is always right in front of us.” Alex frowned. “Almost all the religious prophets have been wrong about the end of times they predicted. We are so coded for negativity bias that it completely blinds us to what is actually going on.”

“Don’t forget homeostasis,” Kira added. “The purple dot problem.”

“Remind me?”

“They did a study with blue and purple colored dots. You were supposed to count how many of each color. At first, they were clearly different and pretty equally split. Then each picture subtly made the colors less different and skewed more toward one color. The people would still select a similar number of blue or purple. Instead of fifty-fifty, it might look like sixty-forty but in reality, it was like eighty percent blue and only twenty percent purple.”

“They’d find a difference or a pattern where none existed,” Alex concluded. “I’m dealing with that now with my research in big data.”

“It’s not a data problem as much as it is an interpretive problem. As racism and sexism vanished from out in the open, ‘blue and purple’ people didn’t see less of it. Maybe only marginally less, because each time they just kept pulling out a finer-toothed comb to maintain homeostasis.”

“That’s why I have to add solid parameters to my data. Some processes have gotten so efficient that the old out-of-condition measures are way out there so it’s tempting to tighten them up. But that would potentially create an out-of-condition incident in the data through artificial constraints.” Alex thought for a moment.

“So, what does that Library of Alexandria in your pocket say about the good things?”

“Hey Jarvis, please provide a table summarizing the latest research on standard of living improvements over the past two hundred years. Provide the statistic along with a quantification of the overall improvement. Provide a second focused on women’s issues.” He paused, “Oh, and list sources in APA format.”

“You named him Jarvis?”

“I love Tony Stark.”

“Fair enough.” Kira leaned forward as ‘Jarvis’ spit out a beautifully formatted table of information. “Think of how long that would have taken us to make this back in college.”

Alex read from the tablet:

“Life expectancy | Increased from around thirty years in the early eighteenth century to over seventy years in the twenty-first century.

“Infant mortality | Decreased from over three hundred deaths per thousand live births in the eighteenth century to less than ten deaths now.

“Extreme poverty | Reduced from around ninety percent of the global population one hundred years ago to less than ten percent.

“Literacy rates | Increased from around twelve percent of the global population to over eighty-six percent in one hundred years.

“Access to education | The average number of years of schooling has increased from two years in the early nineteen hundreds to over eight years. Again in only one hundred years.

“Violent crime rates |Homicide rates have dropped by fifty percent in some Western countries since the Middle Ages.

“War-related deaths |Declined dramatically since the end of World War II, with fewer people dying from wars in this century compared to earlier centuries.

“Rights for women and minorities | Significant improvements in gender equality, racial equality, and LGBTQ+ rights have been achieved over the past few centuries.

“Access to information | The rise of the internet and digital technologies have made information more accessible to a larger portion of the global population than ever before.

“Democracy and human rights | The number of democratic countries has increased from around a dozen in the early twentieth century to more than one hundred now, and the respect for human rights has improved globally.”

“Nice, and for women?”

He continued:

“Female literacy rates | Increased from around six percent of women globally in the eighteen hundreds to over eighty-five percent today.

“Women have achieved near-universal primary education in many countries and female enrollment in secondary education matches males and women now even outnumber men in all levels of college degrees.”

“What about globally?” Kira interjected.

“Same parity and the average number of years of schooling for women has increased from around one year in the early eighteen hundreds to over eight years globally today.”

“Purple dot problem?” Kira considered the information. “I think the bigger issue is that we always think there is more we can do.”

“Well, there is,” Alex said. “I think the problem is when people say nothing has gotten better, or even that it’s gotten worse.”

“I shared a lab for my dissertation with a researcher who had gone to India after college in the nineties as a single woman. She talked about how she had traveled everywhere and it was wonderful.” Kira swirled her drink.

“But when I said I was going to India that summer she was all worried and warned me about how dangerous it was now for me as a woman.” She put the cup down. “When I shared the statistics that violent crime on women was less than a quarter the rate it was in the nineties and even lower for foreign women, she couldn’t accept that was true. She honestly got mad at me and told me I was naïve.”

“When she went there was a significantly higher risk?”

“Yeah, during the time she was there two other university students were attacked and raped, and that hadn’t happened in the ten years before I was going. India wasn’t even close to the same country thirty years later.” Kira put her chin in her hand. “This woman viewed everything as worse, specifically worse for women.”

“When it quantifiably is better in all dimensions.”

“And they wonder why we have such high degrees of anxiety and depression. I think it’s because we are primed for a certain amount of trauma or challenge, and as those purple dots of problems go away, we look harder and harder for them but they aren’t there.”

“And nothing is worse than a problem you are pretty sure exists but you can’t find.” Alex offered.

“We expect the problem, but can’t find it, so our anxiety spikes. Because we can’t prepare for it, we become hypervigilant trying to find the purple dot. We end up convinced the boogie man is out to get us and start claiming all the blue dots are really purple.”

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Check Out Refind: Brain food, delivered daily

Every day, Refind analyzes thousands of articles and sends you only the best, tailored to your interests. Loved by 503,336 curious minds. Subscribe Here

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

- All-around great daily essays

- Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

- Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

- Integrating AI into education

- Computer Science for Everyone

I tend to remind people that the US was established by a political division that caused us to overthrow our ‘legitimate’ government. I also like to remind them about the Civil War which was when 1/2 of the United States seceded because of political division so there’s that to provide context.

Even within this time window you have JFK’s assasination and a lot of other unrest.

I’ve gotten a lot of feedback on these numbers and without a full on edit, I’ll accept my number is lower compared to the expereince of many in extreme areas. I used data from Zillow here: https://www.zillow.com/learn/buying-starter-home/

It does suffer from the bane of averages and that is, it takes out the extremes. But so too does the data from the 1950s. I also picked a much lower point for 1955 as well to not bias the data too much. I’m trying to be applies to applies so taking the lowest from 1955 and the highest from today won’t work.

These numbers also trigger a lot of feelings. It’s insightful to feel a reaction and then square that against the number. For a lot of comments I’ve gotten, they can’t discredit the numbers but it feeeeeeels worse than it was. That feeling is the entire point of the essay. There’s a logical reason we do feel this way and that’s important to understand.

I don’t think you talked about the growth of the bureaucratic state. Everything is recorded now. Everyone has a file.

I was arrested for juvenile delinquency in 1987. Today I’m a licensed professional.

Crimes, truancies, delinquencies - even smoking pot from the 1970s through 2015 would’ve landed you with a criminal record; forever recorded; indelibly, by the bureaucratic state.

Is the spike in crime that you record over the last 60 years truly representative of changes of behavior or is it simply the fact that we got better at recording the activities of teenagers?

I got arrested in 1987 for activities that, 50 years earlier, probably would’ve gotten me whipped by my father or punished informally by local authorities.

I would also strongly recommend Hans Rosling's Factfulness and his videos.