Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and explore them from different perspectives and disciplines, to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic continues a collaboration between

I as we write on the history, culture, and science of our favorite indulgences. Today we’ll explore whisky and you can also look back at our previous “Odes” for more fun and informative insights.An Ode to Chocolate a special collaboration adding in

.

Intro

After a hard day’s work, you’re sitting down in your favorite chair, sipping on your particular water of life. The highball highlights all the taste buds near the back of your mouth with a complex blend of bitter and slightly sour flavors, while the front of your tongue has a delightfully burning twinge.

Notes of oak and… is that butterscotch? Could it be caramel?

After a few sips, you start to feel more relaxed, and after a few more minutes, your comfortable chair begins to feel inescapable.

Ah, whisky!

(Or is it whiskey? We’ll get to that.)

For now, suffice it to say that we (Michael and Andrew) are fans of the history, process, and craft involved with making and drinking whisky (and whiskey). Today, we want to share some of this intoxicating wonder with you, along the lines of our other inebriatingly collaborative an Ode to Beer.

What’s in a Whisky?

As alluded to above, there are two ways to spell whisky, although one of them is used predominantly only in the US and in Ireland (whiskey). When I (Andrew) first became interested in whiskey (it was with that -ey ending), it was one particular type that drew me in: straight bourbon whiskey.

More commonly, we call this bourbon. Bourbon is only made in the United States. No, this is not me being jingoistic, like somehow suggesting that pizza can only be made in America, or that Japan alone can actually make sushi.

No, bourbon can only be made in the US because that’s part of how we define what bourbon is. By definition, bourbon has to be:

brewed and distilled in the US

distilled from at least 51% corn

distilled to an ABV (Alcohol By Volume) of no more than 80%

aged in a barrel at no more than 62.5% ABV

aged in new oak containers with charring on the inside

bottled at 40% ABV or higher (also called 80 proof)

Finally, it has to contain no additional colors or flavors. You can add rye, wheat, or barley to the corn, but you dare not add any other ingredients whatsoever, or else you can’t call it bourbon.

I once heard that bourbon also had to be made in the state of Kentucky, but that’s just an urban legend. However, there is such a thing as Kentucky straight bourbon whiskey, and of course, that has to be made in that particular state.

Now, briefly back to spelling: America spells it with that e, but that’s not exclusive to the United States. The Irish also spell it w-h-i-s-k-e-y, and maybe that shouldn’t be much of a surprise, since early distillers here in the US were largely of Irish descent.

The strong desire to differentiate from our former colonial overlords (the British spell it w-h-i-s-k-y) probably helped to standardize the not-British spelling here, in yet another example of linguistic schismogenesis; using words to differentiate and one-up other people, groups, or cultures.

Everything so far is all about bourbon, but whisky is a lot more encompassing. Whisky includes scotch, Irish whisky, and bourbon, among other types… if you’ve had all three of these most common varieties of whisky, you know how wide of a range the drink comes in. Now, shifting gears slightly, we’ll hand it over to Michael to step back and look at the history and science of distillation in general.

History

We were surprised to learn that evidence of distillation dates back to 1200 BCE in ancient Mesopotamia. At this time it was primarily used for creating perfumes and medicinal substances. The Greeks later advanced the process, and by the 1st century CE, distillation was practiced in Alexandria by alchemists like Zosimos of Panopolis.

The most significant development in the distillation of alcoholic beverages occurred during the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 14th centuries). The Arab alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan designed the alembic still, which allowed for the effective distillation of alcohol.

By the Middle Ages, knowledge of distillation spread to Europe through translations of Arabic texts by scholars like Robert of Chester and Michael Scot. Monasteries became centers of distillation, producing medicinal spirits. It wasn’t until the late 15th century that we saw the advent of whiskey in Ireland and Scotland, initially produced by monks using locally grown grains.

However, it wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution, and the introduction of advanced technologies such as the column still that large-scale production and refining was enabled that created the quality and consistency of spirits as we know it today.

Science of Distilling

There are a couple of interesting twists we’ll explore here as we break down the science of distilling. The first is that the beginning process for whiskey is identical to beer. Namely, we take grains like malted barley, corn, and rye, and steep them in warm water to break the complex carbohydrates down into simple sugars and then add yeast for fermentation.

The only major difference between this pre-whiskey and beer is that beer has the addition of hops and is not distilled. In fact, whiskey, before distillation, is called Distiller’s Beer. While there are some differences in the grain compositions, if we were to stop here, we’d have a non-hoppy, more alcoholic, and flavorful beer. It’s the distillation that creates the transformation.

Distillation is merely the separation of alcohol from the rest of the liquid. Distiller’s Beer is about 15% ABV, similar to wine. That means you have to separate that 15% of alcohol from the other 85% of water.

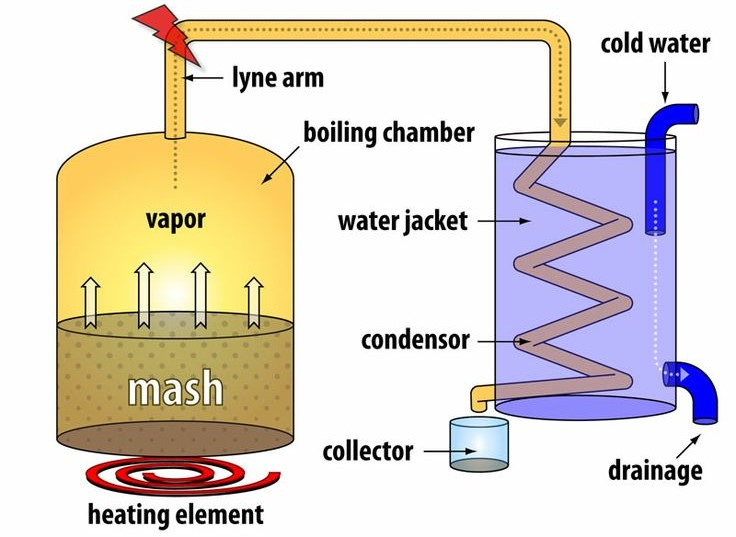

Thankfully, alcohol has a much lower boiling point (around 78.3°C or 172°F) than water, allowing it to vaporize first when heated. At the simplest, you have a pot still where the liquid is heated, the vapor is captured, condensed, and cooled into a distillate. For the sake of brevity, we’ll skip the dozens of still designs and merely state that the different stills do impart different profiles for different styles of drink.

The alcohol we are looking for specifically is ethanol. However, mixed in are also nastier alcohols like methanol and other volatile compounds like acetone. Thankfully, these boil at even lower temperatures and can be separated out.

There are four major distillation stages based on temperature as follows:

Foreshots: The first fraction to evaporate contains methanol and other volatile compounds, starting around 50°C (122°F). These are toxic and discarded.

Heads: Collected next, they include ethanol but also some unwanted compounds like acetone. This fraction is generally taken at temperatures between 60-78°C (140-172°F) and are normally recycled or discarded.

Hearts: The main product, containing the highest quality ethanol and desired flavors, collected between 78-82°C (172-180°F). This is what you buy.

Tails: The last fraction contains higher boiling point compounds like fusel oils, starting around 94°C (201°F) and higher. These can impart unwanted flavors but can be used for further distillation in another batch.

Now that you have this foundation, let’s address a very common misconception that home distilling or moonshine will make you go blind. First off, there is some truth to this because those foreshots contain methanol which the body metabolizes into formaldehyde, a highly toxic chemical which can cause blindness.

So an eager distiller, sampling what comes out of the still first, will get a straight shot of toxic methanol. The only catch is that this foreshot is about 100% alcohol and has all the palatability of turpentine. If they did sample this bit, they’d be in for a horrific experience. If they mixed all the distillate together, they’d still have the same methanol to ethanol ratio as a wine which can’t eliminate the methanol.

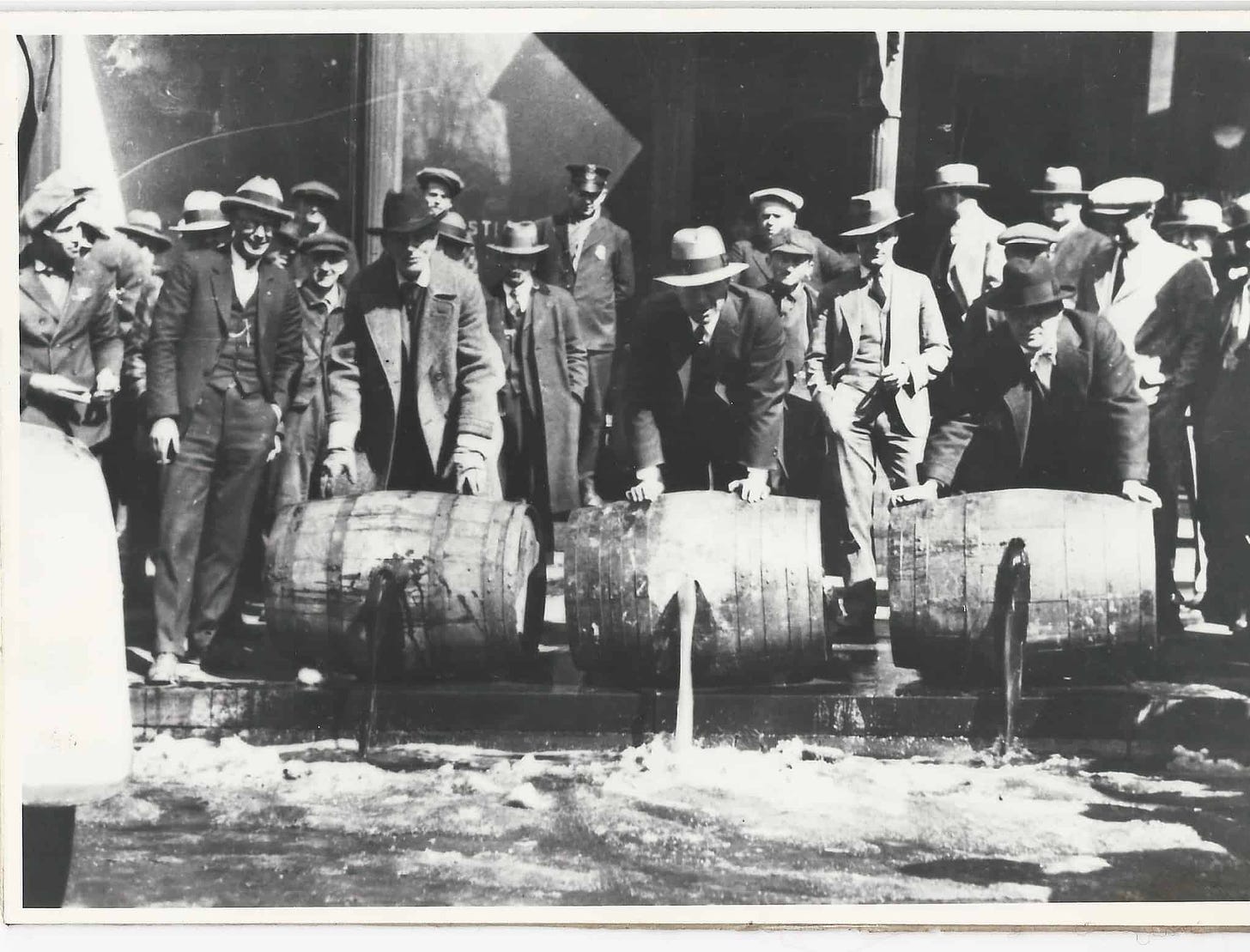

The real story for moonshine making you go blind takes us back to our history lesson where, during prohibition, the US Government intercepted barrels of whiskey on the black market and added formaldehyde in an attempt to poison and scare citizens who frequented the clandestine speakeasies. Simply put, moonshine won’t make you go blind, but the government sure can.

Back to Whiskey. The distillation of the Distiller’s Beer into ethanol looks and tastes almost nothing like the whiskey we are expecting. In fact, the distillate is clear and tastes closer to vodka than bourbon. This is because vodka is what’s called a neutral grain spirit. It’s just pure ethanol cut down to 40% with filtered water.

Fun fact #1: You can make any alcohol into vodka. You can take a 15-year-old Talisker Scotch and distill it into vodka. You can even distill beer into vodka. This is because distillation merely extracts the ethanol. The more you distill, the more pure the ethanol becomes which is why some vodka brags about the number of distillations.

Fun fact #2: Distilling is much more forgiving about the original fermentation than wine or beer. If either of these two gets infected and sour, the product is normally scrapped. Distilling doesn’t care, it’ll extract the ethanol off anything.

Fun Fact #3: If you distill a neutral grain spirit on top of botanicals, you get Gin. That’s all there is to it. A friend’s beer soured and, instead of throwing it out, he distilled it into ethanol and then redistilled it into Gin. Bad beer into Gin, no joke.

Whiskey distillate does retain some of the flavors of the grains but it’s the aging in oak casks that adds back in all the color and flavor we’ve come to expect. This is due to a series of chemical reactions that occur:

Extraction of flavor compounds: Lignin, hemicellulose, and tannin compounds are extracted by the alcohol. Lignin breaks down into vanillin, which imparts vanilla flavors, and other compounds that add clove and smoky notes. Hemicellulose contributes sweetness and complexity, and tannins add bitterness and astringency.

Filtration: The interior of the oak barrels is charred which acts as a filter, removing undesirable elements like sulfides. This smooths out the whiskey.

Oxygenation: Oak barrels are porous, allowing oxygen to interact with the whiskey. This process mellows the spirit and balances the flavors while helping to develop some more complex taste profiles.1

Caramelization: The charred oak caramelizes the wood's natural sugars. This adds both the amber color and rich, sweet flavors to the whiskey.

The longer the whisky stays in the barrels, the more exposure it has to these chemical processes resulting in smoother and more nuanced flavors. This is why a 30-year-old Scotch tastes better than a 10-year-old. It’s also why they’re so much more expensive because time = money.

After barrel aging, the distiller has a choice, do they want to do a blended or single-barrel whiskey? The decision rests on the quality of the individual barrel. Some barrels are better than others and blending them results in a more consistent whisky,2 or you can select the best barrels for a single-barrel offering. This is why single-barrel whiskey fetches a premium over the standard, and more consistent offerings.

If this seems like a lot of work and years of patience, you’re right. Thankfully modern science has figured out how to extract these flavors more quickly and between advanced carbon filtration, pressurization on oak staves, and other tools, you can make what tastes like a 15-year-old bourbon in days with the right equipment.

Even crazier, because of how cool chemistry is, they’ve figured out how to extract the specific flavor compounds into extract packets that you can add to vodka and create a whisky in minutes.

That process might offend our bougie sensibilities but from a chemistry perspective, they’re the same. It just boils down (pun intended) to whether your goal is the flavor of a whisky or the entire process that has historically created our whisky. We’ll leave that decision to you.

Conclusion

We hope this little exploration helps you to appreciate one of our favorite libations with a little more appreciation of the process. As with the other Odes we’ve written, it’s fun to get into the culture, history, and science of the things we love and often take for granted.

We’d love to hear your distilling stories, favorite whisky, or recommendations for what other Ode To topics you think we should explore!

Also, please take a look at

’s substack here:Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Check Out Refind: Brain food, delivered daily

Every day, Refind analyzes thousands of articles and sends you only the best, tailored to your interests. Loved by 503,336 curious minds. Subscribe Here

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

- All-around great daily essays

- Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

- Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

- Integrating AI into education

- Computer Science for Everyone

There’s an interesting consequence of this process as it results in a loss of alcohol, known as the Angel’s Share, which creates Whisky Fungus, a nasty black mold. While it’s always been a bit of a problem, the explosion in popularity of bourbon has literally coated regions in Kentucky with this mold.

I’ll add here that blended scotch, like Johnny Walker Red Label, is mixed from a large variety of other brands of scotch. For instance, Talisker is mixed in which gives Red its distinct smokey flavor over Black and Blue which mix different brands of scotch.

I think there’s something in our consciousness that sees a quick and simple fix, like a flavor packet, thrown into vodka to turn it into whiskey, as some kind of cheat code. Like somehow deep down, we know the process should be long and arduous, much like life itself, in order to create a beautiful end product. Though the outcome might be the same, I’m not sure it will ever be appreciated as much as following the process. Sort of like “the journey is more important than the destination.” However, if my life’s calling is NOT a whisk(ey) maker, and all I want to do is enjoy a glass of bourbon, I don’t care how it’s made. I’ll follow my arduous journey (and find satisfaction in it) elsewhere. Nice write up!

Now this is the stuff that made America great. The history of our country is a path through its early beginning to its recent resurgence.