An Ode to Beer

History, Science, and Culture

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic is another collaboration with Andrew Smith of Goatfury Writes. We partnered recently on An Ode to Coffee where we did a fun historical, cultural, and scientific analysis of one of America’s favorite drinks. This one follows the same recipe and shifts the focus to beer. You’ll also get a sneak peek at my homebrew kegerator that keeps this delicious elixir flowing for friends and family.

The History of Beer

Andrew here. I stopped drinking, cold turkey, about 15 years ago as I was struggling to maintain a healthy balance. Nevertheless, I’ve continued to be fascinated by alcoholic beverages over the last 15 years, and since flavor is no longer the main way I experience them, I’ve turned to history in order to broaden my understanding and appreciation of their importance.

You might be thinking: okay, I know beer has to go back a few hundred years because I’ve heard about monks making beer in abbeys in Europe. So, maybe those origins go back to the medieval or ancient world… I hope you’re sitting down.

I’m here to tell you that humans have been brewing and drinking beer for longer than we’ve been writing. In fact, a clay tablet with some of the earliest known writing records beer given to workers as part of their daily allotment. The invention of beer is far older than the invention of the wheel, and its role in shaping human civilization is among the most important factors.

Jiahu, China makes a decent case for the earliest known beer from 8600 years ago. Pottery shards from a site were analyzed, and alcoholic fermentation was shown to be present. This truly ancient recipe was made from rice, honey, and fruit. Clearly, alcoholic beverages were an important part of human life a long, long time ago.

Maybe you’re reading this and thinking: that’s not beer! You might be right. Beer is currently made from barley, hops, yeast, and water (much more on this in Michael’s section below). Let’s instead call Jiahu-brew “proto-beer.” In historical terms, it is an important example of early humans' experimentation with fermentation, showcasing their understanding of the natural process of yeast converting sugars into alcohol… but it’s at best a stepping stone toward what most folks would consider beer.

Real Beer

The origins of barley-based beer lie in Mesopotamia, around 3400 BCE. 5400 years ago, is still pretty impressive, and its origins might go back even further than that—this is just what we’ve found so far. Its cultural importance is captured in the Sumerian Hymn to Ninkasi, written around 1800 BCE, which sings praise to the Sumerian goddess of beer and brewing. Her name literally means "the woman who fills the mouth." It’s a 3800 year old ode to beer. (We are late to the party)

Ninkasi was an important figure in Sumerian mythology. She was believed to have taught humans how to brew beer and was associated with both positive and negative consequences of drinking beer. Hangover? That’s Ninkasi’s doing. Have an innovative idea while drinking with other folks? Also Ninkasi.

Beer was an important social connector for much of the ancient world and yet it was more than that, too. The Sumerians used beer as a staple part of adult and child diets. Current theory suggests that the alcohol from fermentation provided protection from common bacterial illnesses and also provided a method to preserve essential calories in an environment where grain could spoil quickly.

In ancient Egypt, beer was consumed by both the highest officials and the common people. Records show that workers who built the Great Pyramid of Giza were paid 10 pints a day. I bet waking up to head to work was as tough for these workers as it was for me in my late 20s!

Continued Evolution

The beer that we recognize today required the addition of hops, which didn’t emerge until 9th-century European monks started to add them. Hops give the beer its bitter taste while also helping to prevent spoiling as a natural antimicrobial.

The German Reinheitsgebot (Beer Purity Law) of 1516 limited the ingredients of beer to Barley, Water, Hops, and Yeast and began the standardization of beer as we know it. Coupling that with the Industrial Revolution led to a much more consistent and widespread product and the emergence of many of the old European brands.

An interesting aside is that up until the late 1800s, your beer would have had zero carbonation. That’s because there was no vessel available that could hold in the pressure required to maintain carbonation. Carbonated beer required advanced steel manufacturing for kegs and precision aluminum and glass for cans and bottles that just did not exist until roughly 150 years ago. In fact, the first cans of beer did not appear until 1935! Prior to this, most beer was consumed flat.

Not only flat, but warmer. Refrigeration is also a relatively new invention on the historical scale so beer would be stored in cool, but not cold areas. Europeans, where most of our beers came from, still drink their beer much warmer than the general US population.

By the end of the 19th century, the world was introduced to lagers and pilsners (more on those from Michael below). These beers were easier to produce in large volumes, had light and crisp flavors, and set the stage for the carbonated cans of Budweiser and Miller beers that most of us grew up surrounded by.

Yet a rebellion was fermenting in the 1980s where hobby craft brewers worked diligently in their garages to produce a great variety of beers, focused on the easier-to-brew Ales, and led to the explosion of craft brews in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Today, microbreweries are everywhere. In my town of Richmond, we seem to have more craft breweries per capita than anywhere in the entire country. Maybe I picked a bad time to quit drinking beer after all!

And, with that, I will pass the stein back to Michael.

The Science of Beer

Beer is so simple and yet so complex. For today’s essay, I won’t break down the intimate details of the chemistry but instead, focus on how four simple ingredients can create everything we enjoy in beer.

That’s right, modern beer (typically1) has four ingredients. That’s it. Malted Barley, Water, Hops, and Yeast. With these, we can make almost every beer on the planet. Lest you think these four ingredients are simple, for the avid beer brewer, each ingredient has its own 300-page book! This is where the science becomes interesting. Especially when it comes to the chemistry behind regional beer styles.

Water and Malt

Water is water is water right? Not in the least! This critical ingredient is actually the reason behind regional beer varieties and the passionate homebrewer can not overlook the significance.

Why is Ireland known for Stouts and the Czech Republic known for Pilsners? It all starts with the enzymatic action required to break down the complex carbohydrates in the malted barley into simple sugars for fermentation. This requires a very specific 5.2 pH. Distilled water has a pH of 7 which is considered neutral and so we need an acid to bring the level down slightly. That’s where the malt plays two essential roles in beer.

The first role is to provide the sugar to ferment and the flavor and mouthfeel of the different beers. The sugar is achieved by malting barley, a process where the grain is germinated until it begins to sprout, breaking the complex carbohydrates into simpler ones. This germinated barely is then roasted to different levels from light to dark creating the differences between a Stout and an India Pale Ale.

The roasting not only changes the color and flavor but also the pH. This is the secondary role of malt where dark roasted grains contain a higher acid content and will bring the pH down quickly whereas light-roasted malts do not.

So why Irish Stouts? It’s because Ireland has very alkaline water, meaning the pH is much higher, and requires more acidic, ie dark malt, to bring the pH to that perfect 5.2 for the sugar extraction. Light malts just won’t work for that.

Likewise, Pilsen Czech has water that has a much lower pH and cannot use dark grains without dropping the pH below 5.2 and therefore not extracting the sugars. They were restricted to using only lighter roasted grains. Water, and subsequently malt blends, are the foundation of regional beer styles because a pH of 5.2 must be balanced between the two.

Hops

This flavorful flower is another fascinating ingredient. It’s used to both flavor and preserve beer. Originally, beer was flavored with Gruit, an herb mixture consisting most often of heather, ivy, horehound, mugwort, and yarrow. Gruit was predominantly a bittering agent and would result in a sour beer due to the introduction of the bacteria lactobacillus which creates the tangy flavor in sauerkraut among others.

Hops began being used around 700AD and have the benefit of both flavoring and bittering combined with antimicrobial properties that preserve the beer. Hops are also regionally varied and have been specifically cultivated to balance the bitter Alpha Acids with the aromatic Beta Acids and the essential oils containing additional flavor compounds. Today there are over 250 cataloged varieties of hops to choose from.

The utility of hops also affects the resulting beer. For example, the highly hopped India Pale Ale was done in England so that the increased preservative compounds enabled the beer to survive the long ocean journey to India without spoiling. Ironically, hipsters spoiled many IPAs through their egregious use of hops with zero nuance to the palate. For instance, a hoppy beer requires a higher malt content to balance the flavors. This is why IPAs typically contain a higher alcohol percentage.2

During the brewing, the water and malt, known as wort is boiled with the hops to extract the acids and oils. The longer the hops are boiled, the more bittering agents emerge. As such, beyond just the varieties of hops, there’s also a ton of science (and art) behind how long you boil the hops to balance the flavors.

Yeast

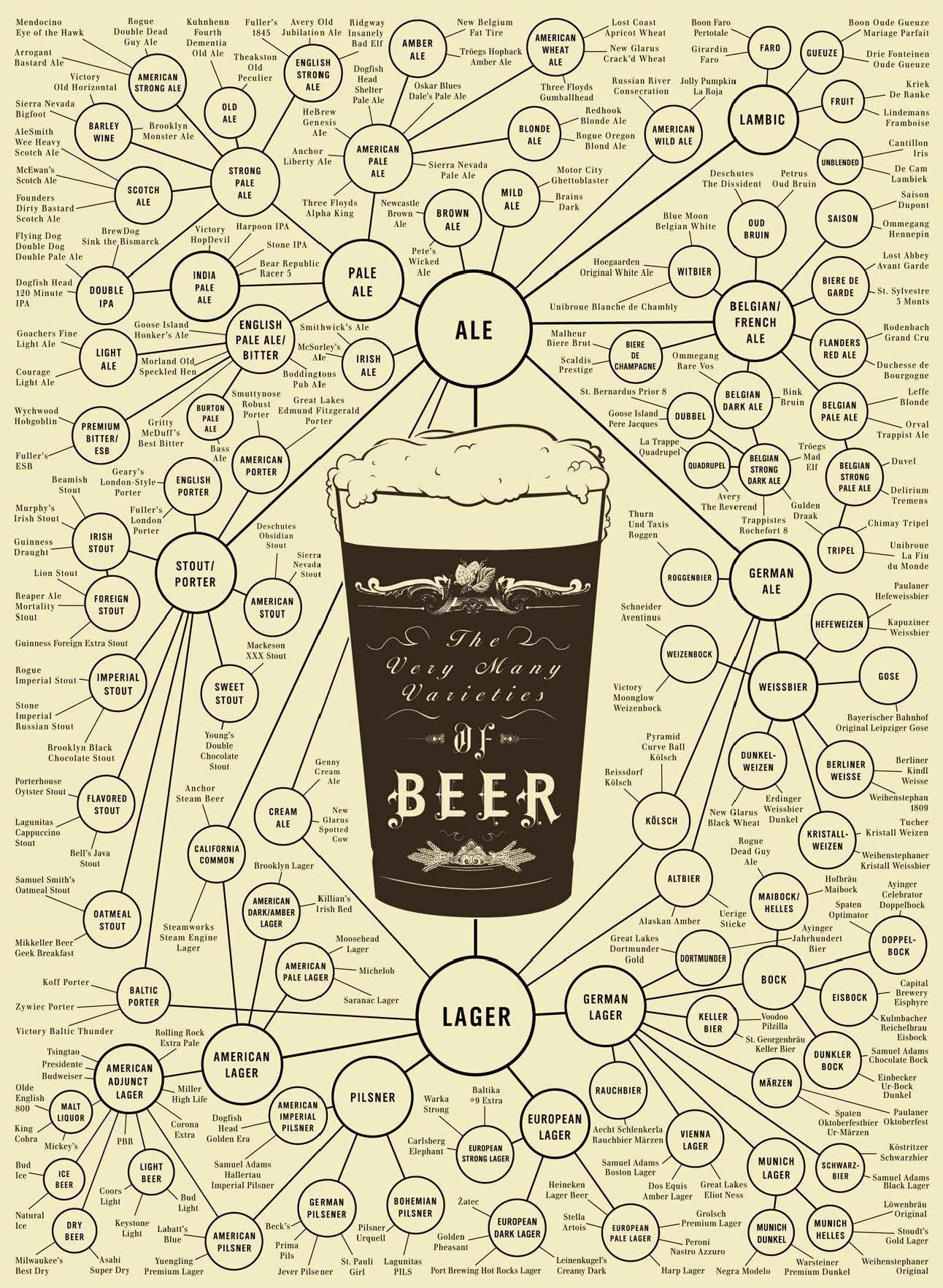

If you’ve been surprised at the simplicity, yet complexity of beer ingredients thus far, yeast should be just as fascinating. Fundamentally, all beers that you know use just two types of yeast. Ale, or top-feeding yeast, and Lager, or bottom-feeding yeast. Many different beers are created through unique strains of these two yeasts.

Yeast creates the flavor difference between the sweet Saison, the crisp IPA, the Hazy IPA, the warm Belgian Trippel, and every flavor in between. Yeast is such a crucial ingredient in the nuanced flavors of different types of beer that breweries treat them as trade secrets and guard them very carefully.

Back to Ale and Lager yeasts, the former likes temperatures of about 65 to 75F and ferments quickly. Ale yeast doesn’t like it too hot, as it will release off-flavors, or too cold, where it stops fermenting. Lager yeast can survive at much lower temperatures and owes its name to the German word for storage as they would ferment the beer over the winter in colder climates.

Of interest, Lager yeast is actually from the Patagonia mountain region in Argentina and resulted from German colonists drinking beer from the homeland, storing the empty casks in the open, and returning them to Germany for refilling. Over time a native Patagonian yeast strain ‘infected’ the casks and, in the early 17th Century, became the strains we use for lagering today.

A new, third variety of yeast has recently entered the homebrewing world from Norway called Kveik. This yeast can handle much higher fermentation temperatures without producing off-flavors making it nice for brewers like me who ferment in hotter climates and don’t always want to temperature control our brews. I’ve experimented with Kveik for a couple of years and am pivoting back to the classic strains. While it works well for certain beers, it lacks the nuanced flavors that an astute connoisseur appreciates.

Summary

All of our current varieties of beer consist of water balanced with regional pH, salts, and minerals, a balanced mixture of malt for flavor, mouthfeel, finish, and a pH of 5.2, a precise selection of hops with intentional timing of the boil, and the yeast that brings it all together. We’ve only scratched the surface of the full science behind beer but hopefully, we’ve provided enough for you to appreciate the complexity next time you enjoy this libation.

Yet throughout history, beer had many other flavors and styles that have been lost to memory. It would be fascinating to step back in time and try a beer from even 1000 years ago and see if it was anything like we are familiar with today.

In closing, I, Michael, would like to show off my kegerator setup in my house. I can say without hyperbole that I designed and built this house around my kegerator. It sits next to the fridge in the kitchen and is plumbed through the wall to a specially fitted closet which holds my kegerator.

It’s a chest freezer fitted with a thermocouple override that maintains a temperature of around 38F. The taps are mounted on a box that allows cool air to circulate via a small computer fan from the kegerator, keeping the lines cool.

Please let us know if you brew or what your favorite beers are in the comments below!

Here’s another in our Ode To series.

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further Reading from Authors I really appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Goatfury Writes All-around great daily essays

Never Stop LearningInsightful Life Tips and Tricks

Cyborgs WritingHighly useful insights into using AI for writing

One Useful ThingPractical AI

Brewers do add a variety of adjunct spices like pepper, citrus, and even fruits like raspberries and strawberries to different beers. I have personally made both an Apple Cider Ale and a Prickle Pear Cream Ale (yes, prickly pear cactus fruit)

If anyone dares suggest they have a Tripple IPA, just slap them in the face for being a fool.

This has been one of my favorite collaborations so far! Beer has such a cool and complex history.

This article was great and that setup is insane! I'm curious, what does kveich taste like?