Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic is a historical exploration of Daylight Saving Time (DST). We dive into the history of time, the surprisingly inconsistent application of DST throughout history and across the world and explore ideas for how we could better align our time zones to our advantage.

The History of Time

Exploring Daylight Saving Time (DST) needs to start by looking at the origins of time-keeping itself. Throughout history, our precision in measuring and marking time has improved in fidelity and capability in measurement. Originally, you’d mark it as simply morning, noon, evening, and night. As the need to segment time increased humans started to apply improved measurement systems that left their lasting legacy on our clocks today.

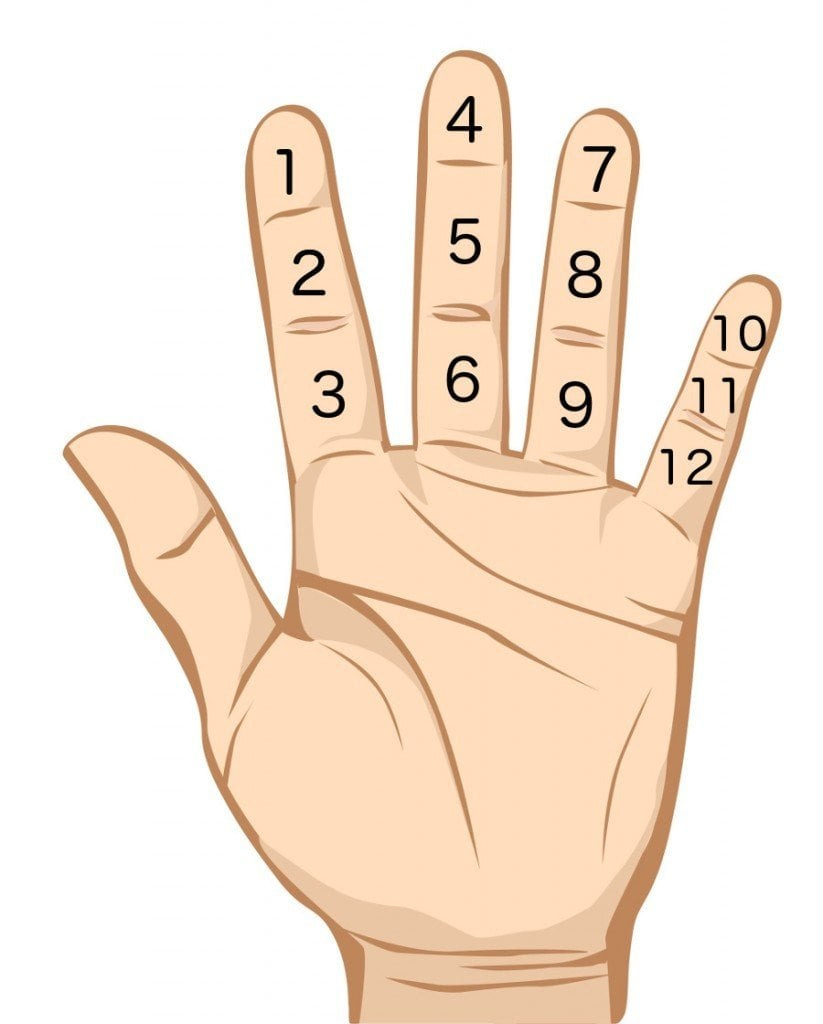

For example, if you ever wondered why we have two, twelve-hour segments that are further divided by increments of sixty, we have the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians to thank due to their duodecimal (base 12) and sexagesimal (base 60) numeral systems. While it might seem simpler to count by base ten, which is our main numbering system today, back in the day base 12 was created by counting on our fingers as well! Except you’d just use your thumb, on your finger joints, to keep count, and since you have 3 joints on each finger, this leads to base 12 counting.

The minutes and seconds come from the Babylonian’s sexagesimal system for astronomical calculations. The base of 60 was created because it’s the smallest number divisible by the first six counting numbers and by 10,12,15, 20, and 30. We see this impact not only on time but also in geometry where a circle has 360 degrees.

However, before precise timekeeping, these measures were still split into 12 daytime, and 12 nighttime hours which work around the equinoxes, but expand and compress towards the solstices and back over time. The 12 summer daytime hours were longer, whereas the 12 winter daytime hours were shorter with the inverse for nighttime hours.

While there was a steady progression in incremental, equal-hour time-keeping with advances over the years from water clocks to incense clocks and many others, it wasn’t until the invention of mechanical clocks in the 14th century that we began to have more clearly delineated and consistent time. Yet, until this point, this precision still really only mattered for religious organizations and specifically the Catholic Church in their Liturgy of the Hours, also known as the Divine Office which demanded more precise timekeeping.

This is one of the main reasons why most of the first clocks were installed in churches. They helped to regulate the daily schedule of prayers and services for the clergy and the faithful, they were a symbol of prestige and wealth for the church and its patrons, and they provided a public service to the community by displaying the time. The English word “clock” first appeared in Middle English and can be traced to the post-classical Latin clocca ('bell'). The precision of time was a benefit for the local community, but this precision was dialed by the solar noon at their location. This worked well until travel and communication became fast enough to require more standardized time zones.

The History of Time Zones

Time zones weren’t needed until the establishment of faster transportation, specifically trains, and the subsequent need for consistent time for arrivals and departures. We can thank the punctual Brits for this because the slight differences in local time between cities would create issues since trains were fast enough that 9:00 AM might be 10 minutes different between east and west train stations. Therefore, the Great Western Railway established common “railway time” in November 1840 and by 1847, most railways were using “London Time,” which was the time set at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

An interesting artifact of the transition from local to standard time exists on the Corn Exchange building in Bristol, England whose clock, installed originally in 1822, has two minute hands just over 10 minutes apart showing both Greenwich Mean Time and Bristol local time.

The use of a standard Greenwich Mean Time is actually older than railway time and was essential, not for timeliness, but for maritime navigation where the measurement of longitude was a tough problem to solve. Determining latitude was relatively easy because it could be calculated from the altitude of the sun at noon but there wasn’t a solution, other than dead reckoning, for longitude (that is the eastward or westward location). In July 1714 the British Parliament passed the Longitude Act and this established a Board of Longitude which offered a £20,000 (~£3,000,000 today) prize for the person who could invent a means of calculating longitude. John Harrison took to the challenge and invented an accurate timepiece that could be used to compare local time to Greenwich time. He produced his working chronometer in 1759 which allowed navigators to know precisely where they are east and west by comparing the time differences. This method was critical to the success of Captain Cook’s circumnavigation in 1772. Today, on maps that use Lat/Long coordinates, the degrees of vertical and horizontal distance are further separated into “minutes” and “seconds” reflecting the original time basis for the measurement.

Sir Sanford Fleming, a Canadian engineer, proposed the use of worldwide time zones in 1878. His idea was to divide the world into 24 time zones that were 15 degrees of longitude apart covering the full 360 degrees of the globe. In 1884, at The International Prime Meridian Conference held in Washington D.C., they established standard time and selected the prime meridian both of which were based on Greenwich Mean Time, and established the 24 time zones. This created 4 time zones in the United States whereas before there were over 144 local times in North America alone!

Enter Daylight Saving

These structured timezones, now divorced from solar noon created a new problem in the world: what to do when you’d rather have more time with light in the evening than in the morning?

While many people suggest it was the farmers who pushed for DST, it was in fact, the non-agrarian folks who wanted it. Farmers have to get up with the sun regardless because animals haven’t learned to tell time yet and a cow is ready to be milked at a consistent time, not specifically at 6 AM.

The main justification for the change, embedded in the word “saving” is that it would help with WWI energy consumption when European nations established DST on April 30, 1916, with the US following on March 19, 1918, with the Standard Time Act. This act was so unpopular in the US however that it was repealed in 1919 and wasn’t reinstituted until February 9, 1942, and called '“War Time” during WWII. This too was of limited duration as it was rescinded again on September 30, 1945. It wasn’t until January 4, 1974, during the energy crises of that decade, that President Nixon signed into law the Emergency Daylight Saving Time Energy Conservation Act of 1973 and formally established DST again.

But DST hasn’t occurred for the same length of time either. It started as six months and was extended to 10 months in 1974 and then back down to 8 months in 1975. It remained from the first Sunday of April to the last Sunday of October, about 7 months, until the Energy Policy Act of 2005. This extended DST from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November, adding 4 weeks and bringing us back to 8 months.

Through all this on-again-off-again of Daylight Saving, whether it was used or not flipped back and forth from federal to local or state decisions creating no small amount of confusion over those periods. In fact, Daylight Saving isn’t consistent even now with Arizona (where I live) not following it, Europe having different dates for their DST, and many other countries, that don’t, or never have abided by it.

What has quickly become clear, is that any saving in energy are limited to dubious at best. A 2011 study found that it cost Indiana residents $9 million per year in increased electricity bills, a 2008 report by the US Department of Energy concluded that extending daylight saving time by four weeks saved only about 0.03 percent of electricity consumption for the year, and a 2016 study by researchers at Yale University and the University of California, Santa Barbara found that daylight saving time increased residential energy use by about 1 percent on average.

What is also clear is that there are significant productivity losses for businesses each time we switch. A study by Chmura Economics & Analytics estimated that daylight saving time costs the U.S. more than $430 million a year. another study by researchers at Cornell University found that daylight saving time increased workplace injuries and decreased productivity in the mining and construction sectors. A third study by researchers at Penn State University found that daylight saving time increased “cyberloafing”, meaning wasting time online instead of working, by about 8 percent on average.

However, while there are interests in getting rid of DST, their answer isn’t to go back to standard time, but to hang on to ‘saving’ time. A bill introduced in the US Senate in 2022 and reinvigorated in 2023 aims to do just this. In fact, Florida voted to ditch the switch in 2018 and retain the summer, nonstandard time but couldn’t implement it because the US Congress only allows maintaining Standard Time. This is why Arizona is the only state who doesn’t follow DST (and we want the sun to go down earlier in the summer so our evenings are cooler anyway)

There is a function of some practicality in maintaining DST year-round where, in American temperate latitudes, the sun rises around 4:30 AM at the summer solstice and sets around 7:30 PM. Since standard clocks and business time were set closer to the equinoxes, and most people are asleep at 4:30 AM, it was seen as more practical to pretend that 4:30 AM is actually 5:30 AM, thereby allowing people to wake close to the sunrise and be active in the evening light.

The vested interests in maintaining DST are mostly around outdoor entertainment like golf whose clientele typically participate after work and so the extra daylight hours into the evening allow greater recreation. When I was in Denmark in August 2022, because it is so far north, it stayed at near daylight brightness until well past 9 PM. It made touring the beautiful city of Aarhus much easier after a day at work. Because of this desire to capitalize on summer daylight hours, in 1895, George Vernon Hudson proposed a two-hour time shift to the Royal Society of New Zealand and although it didn’t pass, it is interesting to consider what benefits an even longer time shift would have.

Summary

It’s interesting to consider that our marking of time is more rooted in archaic methods of keeping time rather than what is most useful for humans. Before precise time-keeping, it didn’t matter when you went to bed or got up. Over the years, we have become incredibly tied to our clocks with school, work, and businesses selecting certain hours for operation. Yet instead of our time being pinned to solar noon, we could adapt, like Hudson suggested, to a two-hour shift, or we could leave it. But what becomes clear are two things. First, it isn’t about saving anything, and second, we shouldn’t keep changing it.

I think it could be really interesting to select a time, in a zone, that best adapts to what those residents deem best. Arizona remains on Standard Time, Florida wants to stay on DST, and there is no reason why this shouldn’t be possible. I just found the whole investigation to be very interesting, much less consistent than I originally thought, and opened an entirely new idea of adapting our time zones.

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Excellent article! We should share this with Neil DeGrasse Tyson. 😁

I liked the thumb pointer to calculate base 12.

I have 3 fingers of beer, e.g. 36 cans, or six 6 packs.